Malayan tapir

| Malayan tapir | |

|---|---|

| |

| Malayan tapir at Tiergarten Nürnberg in Nuremberg, Germany | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Domain: | Eukaryota |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | Tapiridae |

| Genus: | Tapirus |

| Species: | T. indicus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Tapirus indicus | |

| Subspecies[3] | |

| |

| |

| Malayan tapir range | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Acrocodia indica | |

The Malayan tapir (Tapirus indicus), also called Asian tapir, Asiatic tapir, oriental tapir, Indian tapir, piebald tapir, or black-and-white tapir, is the only living tapir species outside of the Americas. It is native to Southeast Asia from the Malay Peninsula to Sumatra. It has been listed as Endangered on the IUCN Red List since 2008, as the population is estimated to comprise fewer than 2,500 mature individuals.[1]

Taxonomy

[edit]The scientific name Tapirus indicus was proposed by Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest in 1819 who referred to a tapir described by Pierre-Médard Diard.[2] Tapirus indicus brevetianus was coined by a Dutch zoologist in 1926 who described a black Malayan tapir from Sumatra that had been sent to Rotterdam Zoo in the early 1920s.[4]

Phylogenetic analyses of 13 Malayan tapirs showed that the species is monophyletic.[5] It was placed in the genus Acrocodia by Colin Groves and Peter Grubb in 2011.[6] However, a comparison of mitochondrial DNA of 16 perissodactyl species revealed that the Malayan tapir forms a sister group together with the Tapirus species native to the Americas. It was the first Tapirus species that genetically diverged from the group, estimated about 25 million years ago in the Late Oligocene.[7]

Description

[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2021) |

The Malayan tapir is easily identified by its markings, most notably the light-colored patch that extends from its shoulders to its hindquarters. Black hair covers its head, shoulders, and legs, while white hair covers its midsection, rear, and the tips of its ears; these white edges around the rims of the outer ear as is true of other tapirs. The disrupted coloration breaks up its outline, providing camouflage by making the animal difficult to recognize against the varied terrain and dense flora of its habitat; potential predators may mistake it for a large rock, rather than prey, when it is lying down to sleep.[8]

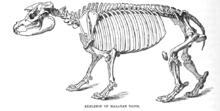

The Malayan tapir is the largest of the four extant tapir species and grows to between 1.8 and 2.5 m (5 ft 11 in and 8 ft 2 in) in length, not counting a stubby tail of only 5 to 10 cm (2.0 to 3.9 in) in length, and stands 90 to 110 cm (2 ft 11 in to 3 ft 7 in) tall. It typically weighs between 250 and 320 kg (550 and 710 lb), although some adults can weigh up to 540 kg (1,190 lb).[9][10][11][12] The females are usually larger than the males. Like other tapir species, it has a small, stubby tail and a long, flexible proboscis. It has four toes on each front foot and three toes on each back foot. The Malayan tapir has rather poor eyesight, but excellent hearing and sense of smell.

The tapir's unique proboscis is supported by several evolutionary adaptations of its skull. It has a large sagittal crest, unusually positioned orbits, an unusually shaped cranium with elevated frontal bones, and a retracted nasal incision as well as retracted facial cartilage. This evolutionary process is believed to have caused the loss of some cartilages, facial muscles, and the bony wall of the tapir's nasal chamber.

Vision

[edit]Malayan tapirs have very poor eyesight, both on land and in water, instead relying heavily on their excellent senses of smell and hearing to navigate and forage. Their eyes are small and, like many herbivores, positioned on the sides of the face. They have brown irises, but the corneas are often covered in a blue haze; this corneal cloudiness is thought to be caused by repetitive exposure to light. This loss of transparency impacts the ability of the cornea to transmit and focus outside light as it enters the eye, impairing the animal's overall vision. As these tapirs are most active at night on top of having poor eyesight, this habit may make it harder for them to search for food and avoid predators.[13][14]

Color variation

[edit]Two melanistic Malayan tapirs were observed in Jerangau Forest Reserve in Malaysia in 2000.[15] A black Malayan tapir was also recorded in Tekai Tembeling Forest Reserve in Pahang state in 2016.[16]

Distribution and habitat

[edit]The Malayan tapir lives throughout the tropical lowland rainforests of Southeast Asia, including Sumatra in Indonesia, Peninsular Malaysia, Myanmar, and Thailand.

Pleistocene fossils were found in Java and other locations accompanied by herbivores more typical of grasslands, indicating that it evolved in more open habitats and retreated to closed forests in later times. It was found in Borneo until at least 8,000 years ago during the early Holocene in the Niah Caves of Sarawak, and some 19th century writers mentioned it as a contemporary species in Borneo, likely based on native accounts.[17] It has been proposed to reintroduce the tapir to the island as a conservation measure.[18][19]

In the continent, the Malayan tapir was found in historical times as far north as China.[20]

Behaviour and ecology

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (December 2021) |

Malayan tapirs are primarily solitary, marking out large tracts of land as their territory, though these areas usually overlap with those of other individuals. Tapirs mark out their territories by spraying urine on plants, and they often follow distinct paths which they have bulldozed through the undergrowth.[citation needed] Exclusively herbivorous, the animal forages for the tender shoots and leaves of more than 115 species of plants, of which around 30 are particularly preferred, moving slowly through the forest and pausing often to eat and note the scents left behind by other tapirs in the area.[21] The tapir can run quickly when threatened or frightened, and if forced to fight can defend itself with its strong jaws and sharp teeth. Malayan tapirs communicate with high-pitched squeaks and whistles. They usually prefer to live near water and often bathe and swim, and they are also able to climb steep slopes. Tapirs are mainly active at night, though they are not exclusively nocturnal; because they tend to eat soon after sunset or before sunrise, and they will often nap in the middle of the night, they are considered to be crepuscular animals.

Life cycle

[edit]

The gestation period of the Malayan tapir is about 390–395 days, after which a single calf is born that weighs around 6.8 kg (15 lb). Malayan tapirs are the largest of the four tapir species at birth and tend to grow more quickly than their relatives.[22] Young tapirs of all species have brown hair with white stripes and spots, a pattern that enables them to hide effectively in the dappled light of the forest. This baby coat fades into adult coloration between four and seven months after birth. Weaning occurs between six and eight months of age, at which time the babies are nearly full-grown, and the animals reach sexual maturity around age three. Breeding typically occurs in April, May or June, and females generally produce one calf every two years. Malayan tapirs can live up to 30 years, both in the wild and in captivity.[citation needed]

Predators

[edit]Because of its size, the Malayan tapir has few natural predators, and even reports of killings by tigers (Panthera tigris) are scarce.[23] Malayan tapirs can defend themselves with their very powerful bite; in 1998, the bite of a captive female Malayan tapir severed off a zookeeper's left arm at the mid-bicep, likely because she stood between her and her offspring.[24]

Threats

[edit]The main threats to the Malayan tapir are loss and destruction of habitat through deforestation. Large tracts of forests in Thailand and Malaysia have been converted for planting oil palms.[1] Habitat fragmentation in peninsular Malaysia caused displacement of 142 Malayan tapirs between 2006 and 2010; some were rescued and relocated, while 15 of them were killed in vehicle collisions.[25]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Traeholt, C.; Novarino, W.; bin Saaban, S.; Shwe, N.M.; Lynam, A.; Zainuddin, Z.; Simpson, B. & bin Mohd, S. (2016). "Tapirus indicus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T21472A45173636. Retrieved 16 January 2022.

- ^ a b Desmarest, A.G. (1819). "Tapir l'inde, Tapirus indicus". Nouveau dictionnaire d'histoire naturelle, appliquée aux arts, à l'agriculture, à l'économie rurale et domestique, à la médecine. Vol. 32. Paris: Deterville. p. 458. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.20211.

- ^ Grubb, P. (2005). "Species Tapirus indicus". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M (eds.). Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 633. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ^ Kuiper, K. (1926). "On a black variety of the Malay tapir (Tapirus indicus)". Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. 96: 425–426. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1926.tb08105.x.

- ^ Rovie-Ryan, J.J.; Traeholt, C.; Marilyn, J.E.; Zainuddin, Z.Z.; Mohd Sharif, K.; Elagupillay, S.; Mohd Farouk, M.Y.; Abdullah, A.A. & Cornelia, C.S. (2008). "Sequence variation in Malayan tapir (Tapirus indicus) inferred using partial sequences of the cytochrome b segment of the mitochondrial DNA". Journal of Wildlife and Parks. 25: 16–18.

- ^ Groves, C. & Grubb, P. (2011). "Acrocodia indica". Ungulate taxonomy. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 20. ISBN 9781421400938.

- ^ Steiner, C.C. & Ryder, O.A. (2011). "Molecular phylogeny and evolution of the Perissodactyla". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society. 163 (4): 1289–1303. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00752.x.

- ^ "Woodland Park Zoo Animal Fact Sheet: Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus)". Archived from the original on September 24, 2006.

- ^ Wilson & Burnie, Animal: The Definitive Visual Guide to the World's Wildlife. DK ADULT (2001), ISBN 978-0-7894-7764-4

- ^ Tapirus indicus, Animal Diversity Web

- ^ Asian Tapir Archived 2014-12-21 at the Wayback Machine,|Arkive

- ^ "Malayan tapir". www.ultimateungulate.com.

- ^ Witmer, Lawrence M.; Sampson, Scott D.; Solounias, Nikos (2001-02-27). "Cambridge Journals Online - Abstract". Journal of Zoology. 249 (3). Journals.cambridge.org: 249–267. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1999.tb00763.x. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ^ "Tapirus terrestris (lowland tapir)". Digimorph. 2002-02-08. Retrieved 2011-01-15.

- ^ Mohd, Azlan J. (2002). "Recent observations of melanistic Tapirs in Peninsular Malaysia" (PDF). Tapir Conservation. 11 (1): 27–28. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-06-25. Retrieved 2006-06-15.

- ^ Asrulsani, J.; Amri, I.; Rafhan, H.; Samsuddin, S.; Saharudin, M.H.; Seman, M.F.; Syafiq, M.; Nasri, M.F. & Patah, P.A. (2017). "Discovery of melanistic Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus var. brevetianus) in Tekai Tembeling Forest Reserve" (PDF). Journal of Wildlife and Parks. 32: 79–83.

- ^ Cranbrook, E. O.; Piper, P. J. (2009). "Borneo records of Malay tapir, Tapirus indicus Desmarest: a zooarchaeological and historical review". International Journal of Osteoarchaeology. 19 (4): 491–507. doi:10.1002/oa.1015.

- ^ Cranbrook, E. O., & Piper, P. J. (2013). Paleontology to policy: the Quaternary history of Southeast Asian tapirs (Tapiridae) in relation to large mammal species turnover, with a proposal for conservation of Malayan tapir by reintroduction to Borneo. Integrative Zoology, 8(1), 95–120.

- ^ Piper, P. J., & Cranbrook, E. O. (2007). The potential of large protected plantation areas for the secure re-introduction of Borneo’s lost ‘megafauna’: a case for the Malay tapir Tapirus indicus. In Proceedings of the Regional Conference of Biodiversity Conservation in Tropical Planted Forests in Southeast Asia. Forest Department, Kuching, Malaysia (pp. 184–191).

- ^ Jarus, O. (2023). "2,200-year-old remains of sacrificed giant panda and tapir discovered near Chinese emperor's tomb". Livescience. Retrieved 2024-06-06.

- ^ Mohd Khan bin Momin Khan (1997). "Status and Action Plan of the Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus)". IUCN Tapir Specialist Group. p. 1. Archived from the original on 2 December 1998.

- ^ Fahey, B. 1999. "Tapirus indicus" (Online), Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved June 16, 2006.

- ^ Mohd Khan bin Momin Khan (1997). Status and Action Plan of the Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus). IUCN Tapir Specialist Group. p. 2. Archived from the original on 29 January 1999.

- ^ Money, J. (1998). "Zookeeper Loses Arm In Mauling at City Zoo". The Oklahoman. Retrieved July 5, 2024.

- ^ Magintan, David; Traeholt, Carl & Karuppannan, Kayal V. (2012). "Displacement of the Malayan Tapir (Tapirus indicus) in Peninsular Malaysia from 2006 to 2010". Tapir Conservation. 21 (29): 13–17.

External links

[edit] Media related to Tapirus indicus at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Tapirus indicus at Wikimedia Commons- ARKive – images and movies of the Asian tapir (Tapirus indicus)

- Tapir Specialist Group – Malayan Tapir