The Tell-Tale Heart

| "The Tell-Tale Heart" | |

|---|---|

| Short story by Edgar Allan Poe | |

The Pioneer, Vol. I, No. I, Drew and Scammell, Philadelphia, January, 1843 | |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Genre(s) | Horror, Gothic Literature |

| Publication | |

| Published in | The Pioneer |

| Publication type | Periodical |

| Publisher | James Russell Lowell |

| Media type | Print (periodical) |

| Publication date | January 1843 |

"The Tell-Tale Heart" is a short story by American writer Edgar Allan Poe, first published in 1843. It is told by an unnamed narrator who endeavors to convince the reader of his sanity while simultaneously describing a murder he committed. The victim was an old man with a filmy pale blue "vulture-eye", as the narrator calls it. The narrator emphasizes the careful calculation of the murder, attempting the perfect crime, complete with dismembering the body in the bathtub and hiding it under the floorboards. Ultimately, the narrator's actions result in him hearing a thumping sound, which he interprets as the dead man's beating heart.

The story was first published in James Russell Lowell's The Pioneer in January 1843. "The Tell-Tale Heart" is often considered a classic of the Gothic fiction genre and is one of Poe's best known short stories.

The specific motivation for murder (aside from the narrator's hatred of the old man's eye), the relationship between narrator and old man, the gender of the narrator, and other details are left unclear. The narrator denies having any feelings of hatred or resentment for the man who had, as stated, "never wronged" him. He also denies having killed for greed.

Critics have speculated that the old man could be a father figure, the narrator's landlord, or that the narrator works for the old man as a servant, and that perhaps his "vulture-eye" represents a veiled secret or power. The ambiguity and lack of details about the two main characters stand in contrast to the specific plot details leading up to the murder.

Plot summary

[edit]

"The Tell-Tale Heart" is a first-person narrative told by an unnamed narrator. Despite insisting that he is sane, the narrator suffers from a disease (nervousness) which causes "over-acuteness of the senses".

The old man, with whom the narrator lives, has a clouded, pale, blue "vulture-like" eye, which distresses and manipulates the narrator so much that he plots to murder the old man, despite also insisting that he loves the old man and has never felt wronged by him. The narrator is insistent that this careful precision in committing the murder proves that he cannot possibly be insane. For seven nights, the narrator opens the door of the old man's room to shine a sliver of light onto the "evil eye." However, the old man's vulture-eye is always closed, making it impossible to "do the work," thus making the narrator go further into distress.

On the eighth night, the old man awakens after the narrator's hand slips and makes a noise, interrupting the narrator's nightly ritual. The narrator does not draw back and after some time, decides to open the lantern. A single thin ray of light shines out and lands precisely on the "evil eye," revealing that it is wide open. The narrator hears the old man's heart beating, which only gets louder and louder. This increases the narrator's anxiety to the point where he decides to strike. He jumps into the room and the old man shrieks once before he is killed. The narrator then dismembers the body and conceals the pieces under the floorboards, ensuring the concealment of all signs of the crime. Even so, the old man's scream during the night causes a neighbor to summon the police, who the narrator invites in to look around. The narrator claims that the scream heard was his own in a nightmare and that the old man is absent in the country. Confident that they will not find any evidence of the murder, the narrator brings chairs for them and they sit in the old man's room. The chairs are placed on the very spot where the body is concealed; the police suspect nothing, and the narrator has a pleasant and easy manner.

The narrator begins to feel uncomfortable and notices a ringing in his ears. As the ringing grows louder, the narrator concludes that it is the heartbeat of the old man coming from under the floorboards. The sound increases steadily to the narrator, though the officers do not seem to hear it. Terrified by the violent beating of the heart and convinced that the officers are aware of not only the heartbeat but also the narrator's guilt, the narrator breaks down and confesses. The narrator tells them to tear up the floorboards to reveal the remains of the old man's body.

Publication history

[edit]

"The Tell-Tale Heart" was first published in January 1843 in the inaugural issue of The Pioneer: A Literary and Critical Magazine, a short-lived Boston magazine edited by James Russell Lowell and Robert Carter who were listed as the "proprietors" on the front cover. The magazine was published in Boston by Leland and Whiting and in Philadelphia by Drew and Scammell.

Poe was likely paid $10 (equivalent to $327 in 2023) for the story.[2] Its original publication included an epigraph that quoted Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's poem "A Psalm of Life."[3] The story was slightly revised when republished on August 23, 1845, edition of the Broadway Journal. That edition omitted Longfellow's poem because Poe believed it was plagiarized.[3] "The Tell-Tale Heart" was reprinted several more times during Poe's lifetime.[4]

Analysis

[edit]"The Tell-Tale Heart" uses an unreliable narrator. The exactness with which the narrator recounts murdering the old man, as if the stealthy way in which he executed the crime was evidence of his sanity, reveals his monomania and paranoia. The focus of the story is the perverse scheme to commit the perfect crime.[5] One interpretation is that Poe wrote the narrator in a way that "allows the reader to identify with the narrator".[6]

The narrator of "The Tell-Tale Heart" is generally assumed to be a male. However, some critics have suggested a woman may be narrating; no pronouns are used to clarify one way or the other.[7] The story starts in medias res, opening with a conversation already in progress between the narrator and another person who is not identified in any way. It has been speculated that the narrator is confessing to a prison warden, a judge, a reporter, a doctor, or a psychiatrist.[8] In any case, the narrator tells the story in great detail.[9] What follows is a study of terror but, more specifically, the memory of terror as the narrator is retelling events from the past.[10] The first word of the story, "True!", is an admission of his guilt, as well as an assurance of reliability.[8] This introduction also serves to gain the reader's attention.[11] Every word contributes to the purpose of moving the story forward, exemplifying Poe's theories about the writing of short stories.[12]

The story is driven not by the narrator's insistence upon his "innocence," but by his insistence on his sanity. This, however, is self-destructive, because in attempting to prove his own sanity, he fully admit that he is guilty of murder.[13] Their denial of insanity is based on his systematic actions and precision, as he provide a rational explanation for irrational behavior.[9] This rationality, however, is undermined by his lack of motive ("Object there was none. Passion there was none"). Despite this, he says, the idea of murder "haunted me day and night."[13] It is difficult to fully understand the narrator's true emotions about the blue-eyed man because of this contradiction. E. Arthur Robinson says that "At the same time he disclosed a deep psychological confusion", referring to the narrator’s comment that there was no object to the murder and that it haunted him day and night. [14]

The story's final scene shows the result of the narrator's feelings of guilt. Like many characters in Gothic fiction, he allow his nerves to dictate his nature. Despite his best efforts at defending his actions, his "over-acuteness of the senses"; which helps him hear the heart beating beneath the floorboards, is evidence that he is truly mad.[15] The guilt in the narrator can be seen when the narrator confessed to the police that the body of the old man was under the floorboards. Even though the old man was dead, the body and heart of the dead man still seemed to haunt the narrator and convict him of the act. "Since such processes of reasoning tend to convict the speaker of madness, it does not seem out of keeping that he is driven to confession", according to scholar Arthur Robinson.[14] Poe's contemporaries may well have been reminded of the controversy over the insanity defense in the 1840s.[16] The confession can be due to a concept called "Illusion of transparency". According to the "Encyclopedia of Social Psychology", "Poe's character falsely believes that some police officers can sense his guilt and anxiety over a crime he has committed, a fear that ultimately gets the best of him and causes him to give himself up unnecessarily".[17]

The narrator claims to have a disease that causes hypersensitivity. A similar motif is used for Roderick Usher in "The Fall of the House of Usher" (1839) and in "The Colloquy of Monos and Una" (1841).[18] It is unclear, however, if the narrator actually has very acute senses, or if it is merely imagined. If this condition is believed to be true, what is heard at the end of the story may not be the old man's heart, but deathwatch beetles. The narrator first admits to hearing deathwatch beetles in the wall after startling the old man from his sleep. According to superstition, deathwatch beetles are a sign of impending death. One variety of deathwatch beetle raps its head against surfaces, presumably as part of a mating ritual, while others emit ticking sounds.[18] Henry David Thoreau observed in an 1838 article that deathwatch beetles make sounds similar to a heartbeat.[19] The discrepancy with this theory is that the deathwatch beetles make a "uniformly faint" ticking sound that would have kept at a consistent pace but as the narrator drew closer to the old man the sound got more rapid and louder which would not have been a result of the beetles.[20] The beating could even be the sound of the narrator's own heart. Alternatively, if the beating is a product of the narrator's imagination, it is that uncontrolled imagination that leads to their own destruction.[21]

It is also possible that the narrator has paranoid schizophrenia. Paranoid schizophrenics very often experience auditory hallucinations. These auditory hallucinations are more often voices, but can also be sounds.[22] The hallucinations do not need to derive from a specific source other than one's head, which is another indication that the narrator is suffering from such a psychological disorder.[20]

The relationship between the old man and the narrator is ambiguous. Their names, occupations, and places of residence are not given, contrasting with the strict attention to detail in the plot.[23] The narrator may be a servant of the old man's or, as is more often assumed, his son. In that case, the "vulture-eye" of the old man as a father figure may symbolize parental surveillance or the paternal principles of right and wrong. The murder of the eye, then, is removal of conscience.[24] The eye may also represent secrecy: only when the eye is found open on the final night, penetrating the veil of secrecy, is the murder carried out.[25]

Richard Wilbur suggested that the tale is an allegorical representation of Poe's poem "To Science", which depicts a struggle between imagination and science. In "The Tell-Tale Heart", the old man may thus represent the scientific and rational mind, while the narrator may stand for the imaginative.[26]

Adaptations

[edit]- The earliest acknowledged adaptation of "The Tell-Tale Heart" was in a 1928 20-minute American silent film of that title[27] co-directed by Leon Shamroy and Charles Klein, and starring Otto Matieson as "The Insane", William Herford as "The Old Man" with Charles Darvas and Hans Fuerberg as "Detectives". It was faithful to the original tale,[7] unlike future television and film adaptations which often expanded the short story to full-length feature films.[28][unreliable source?]

- The earliest known "talkie" adaptation was a 1934 version filmed at the Blattner Studios, Elstree, by Clifton-Hurst Productions, directed by Brian Desmond Hurst and starring Norman Dryden. This version was 55 minutes in length.

- A 1941 live-action adaptation starred Joseph Schildkraut and was the directorial debut of Jules Dassin. This version differs greatly from the original tale, depicting the murderer as driven mad after suffering years of abuse by the hateful older man.

- A 1947 Polish film Zdradzieckie serce by Jerzy Zarzycki was never released.

- A 1953 animated short film produced by United Productions of America and narrated by James Mason is included among the list of films preserved in the United States National Film Registry.

- Also in 1953, an EC Comics adaptation of "The Tell-Tale Heart" entitled "Sleep No More", written by William Gaines and Al Feldstein and illustrated by George Evans (cartoonist) appeared in Shock SuspenStories.[29]

- In 1956, an adaptation of "The Tell-Tale Heart" was written by William Templeton for the NBC Matinee Theater and aired on 6 November 1956.

- A 1960 film adaptation adds a love triangle to the story.

- An Australian ballet was based on the story, and was recorded for television in the early 1960s.[30]

- In 1968, ITV broadcast a television adaptation as part of the horror anthology series Mystery and Imagination. No recordings of the production are known to exist.

- In 1970, Vincent Price included a solo recitation of the story in the anthology film An Evening of Edgar Allan Poe.

- A 1971 film adaptation directed by Steve Carver, and starring Sam Jaffe as the old man.

- CBS Radio Mystery Theater performed an adaptation of the story in 1975; the cast included Fred Gwynne.

- In the 1970s, Stephen King wrote "The Old Dude's Ticker", a short story variously described by King as "satire", "affectionate homage", "pastiche", and "a crazed revisionist telling" of "The Tell-Tale Heart".[31]

- The Canadian radio program Nightfall presented an adaptation on August 1, 1980.

- A musical adaptation performed by The Alan Parsons Project was released on their 1976 debut album Tales of Mystery and Imagination, and was later covered by Slough Feg for their 2010 album, The Animal Spirits.

- Steven Berkoff adapted the story in 1991, and was broadcast on British television. This adaptation was originally presented on British TV as part of the acclaimed series "Without Walls".

- The song "Ol' Evil Eye" off of the 1995 album Riddle Box by the Insane Clown Posse adapts a version of the story, as well as sampling audio from a reading of the original story.

- The Radio Tales series produced The Tell-Tale Heart for National Public Radio in 1998. The story was performed by Winifred Phillips along with music composed by her.

- The 1999 episode of SpongeBob SquarePants entitled "Squeaky Boots" loosely adapts the short story. In the episode, SpongeBob's new boots that squeak with each step stand in for the old man's beating heart. Mr. Krabs hides the boots under the floorboards of the Krusty Krab.

- The film Nightmares from the Mind of Poe (2006) adapts "The Tell-Tale Heart" along with "The Cask of Amontillado", "The Premature Burial" and "The Raven".

- In 2008, filmmaker Robert Eggers adapted the story as a short. This production was notable for using a lifelike, human-sized puppet to portray the old man. Eggers was largely unknown when he made the short, but it garnered attention when he released it online in 2022, after he had achieved some renown as a director of features.[32]

- The 2009 thriller film Tell-Tale, produced by Ridley Scott and Tony Scott, credits Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart" as the basis for the story of a man being haunted by his donor's memories, after a heart transplant.[33][unreliable source?]

- V. H. Belvadi's 2012 short film, Telltale, credits Poe's "The Tell-tale Heart" as its inspiration and uses some dialog from the original work.

- Poe's Tell-Tale Heart: The Game, is a 2013 mobile game adaptation in which players enact the protagonist's actions to recreate Poe's story on Google Play[34] and Apple iOS.

- The 2015 animated anthology Extraordinary Tales includes "The Tell-Tale Heart", narrated by Bela Lugosi.

- The 2015 Lifetime movie The Murder Pact, starring Alexa Vega, is based on Poe's work and incorporates allusions to it, such as the "vulture eye" from "The Tell-Tale Heart".[35]

- In April 2016, a film adaption directed by John Le Tier was released, entitled The Tell-Tale Heart. It starred Peter Bogdanovich, Rose McGowan, and Patrick Flueger in the lead role. It featured a full narration of Poe's story with added elements imagining the narrator as a former tortured soldier with PTSD.

- Redrum (2018), an Indian Hindi-language film, adapts the story.[36]

- In December 2018, Anthony Neilson's stage adaptation was presented at London's National Theatre.[37]

- In September 2022, DijitMedia released an adaptation entitled Edgar Allan Poe's Tell-Tale Heart.[38] It featured the protagonist as a female house-servant to the old man, as was common in the United States during the 19th century.[39] Elements from "The Black Cat" were included to highlight the similarities between the actions of the protagonists.

- In October 2023, "Tell-Tale Heart" was loosely adapted for the fifth episode of the Netflix series The Fall of the House of Usher.

References

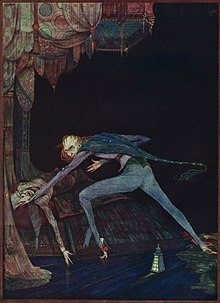

[edit]- ^ "Tales of mystery and imagination". www.vam.ac.uk. Retrieved 21 October 2024.

- ^ Silverman, Kenneth. Edgar A. Poe: Mournful and Never-ending Remembrance. New York: Harper Perennial, 1991. ISBN 0-06-092331-8, p. 201.

- ^ a b Moss, Sidney P. Poe's Literary Battles: The Critic in the Context of His Literary Milieu. Southern Illinois University Press, 1969. p. 151

- ^ ""The Tales of Edgar Allan Poe" (index)". eapoe.org. The Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore. September 30, 2007. Retrieved 2007-11-05.

- ^ Kennedy, J. Gerald. Poe, Death, and the Life of Writing. Yale University Press, 1987. p. 132; ISBN 0-300-03773-2

- ^ Bynum, P.M. (1989) "Observe How Healthily – How Calmly I Can Tell You the Whole Story": Moral Insanity and Edgar Allan Poe's 'The Tell-Tale Heart'. In: Amrine F. (eds) Literature and Science as Modes of Expression. Boston Studies in the Philosophy of Science, vol 115. Springer, Dordrecht. doi:10.1007/978-94-009-2297-6_8.

- ^ a b Sova, Dawn B. Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York City: Checkmark Books, 2001: 234. ISBN 0-8160-4161-X

- ^ a b Benfey, Christopher. "Poe and the Unreadable: 'The Black Cat' and 'The Tell-Tale Heart'", in New Essays on Poe's Major Tales, Kenneth Silverman, ed. Cambridge University Press, 1993. ISBN 978-0-521-42243-7, p. 30.

- ^ a b Cleman, John. "Irresistible Impulses: Edgar Allan Poe and the Insanity Defense", in Bloom's BioCritiques: Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Harold Bloom. Philadelphia: Chelsea House Publishers, 2002. ISBN 0-7910-6173-6, p. 70.

- ^ Arthur Hobson Quinn. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9. p. 394

- ^ Meyers, Jeffrey. Edgar Allan Poe: His Life and Legacy. Cooper Square Press, 1992. p. 101. ISBN 0-8154-1038-7

- ^ Arthur Hobson Quinn. Edgar Allan Poe: A Critical Biography. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998. p. 394. ISBN 0-8018-5730-9

- ^ a b Robinson, E. Arthur. "Poe's 'The Tell-Tale Heart'" in Twentieth Century Interpretations of Poe's Tales, edited by William L. Howarth. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall Inc., 1971, p. 94.

- ^ a b Robinson, E. Arthur (1965). "Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart"". University of California Press. 19 (4): 369–378. doi:10.2307/2932876. JSTOR 2932876.

- ^ Fisher, Benjamin Franklin. "Poe and the Gothic Tradition", in The Cambridge Companion to Edgar Allan Poe, edited by Kevin J. Hayes. Cambridge University Press, 2002. ISBN 0-521-79727-6, p. 87.

- ^ Cleman, Bloom's BioCritiques, p. 66.

- ^ Baumeister, Roy F.; Vohs, Kathleen D. (2007). Encyclopedia of Social Psychology. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications, Inc. p. 458. ISBN 9781412916707. ISBN 9781452265681

- ^ a b Reilly, John E. "The Lesser Death-Watch and "'The Tell-Tale Heart' Archived December 18, 2009, at the Wayback Machine", in The American Transcendental Quarterly. Second Quarter, 1969.

- ^ Robison, E. Arthur. "Thoreau and the Deathwatch in Poe's 'The Tell-Tale Heart'", in Poe Studies, vol. IV, no. 1. June 1971. pp. 14–16

- ^ a b Zimmerman, Brett (1992). ""Moral Insanity" or Paranoid Schizophrenia: Poe's "The Tell-Tale Heart"". Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature. 25 (2): 39–48. JSTOR 24780617.

- ^ Eddings, Dennis W. "Theme and Parody in 'The Raven'", in Poe and His Times: The Artist and His Milieu, edited by Benjamin Franklin Fisher IV. Baltimore: The Edgar Allan Poe Society, 1990. ISBN 0-9616449-2-3, p. 213.

- ^ Zimmerman, Brett. "'Moral Insanity' or Paranoid Schizophrenia: Poe's 'The Tell-Tale Heart.'" Mosaic: A Journal for the Interdisciplinary Study of Literature, vol. 25, no. 2, 1992, pp. 39–48. JSTOR 24780617.

- ^ Benfey, New Essays, p. 32.

- ^ Hoffman, Daniel. Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe Poe. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1972. ISBN 0-8071-2321-8, p. 223.

- ^ Benfey, New Essays, p. 33.

- ^ Benfey, New Essays, pp. 31–32.

- ^ Workman, Christopher; Howarth, Troy (2016). Tome of Terror: Horror Films of the Silent Era. Midnight Marquee Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-1936168-68-2.

- ^ "IMDb Title Search: The Tell-Tale Heart". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved 2007-09-01.

- ^ "Sleep No More", by Bill Gaines and Ed Feldstein, Shock SuspenStories, April 1953.

- ^ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2016-05-18. Retrieved 2015-05-01.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ^ "The Old Dude's Ticker". StephenKing.com. Retrieved October 19, 2022.

- ^ "IndieWire: Watch Robert Eggers Adapt Edgar Allan Poe in Early Short Film 'The Tell-Tale Heart'". 28 April 2022. Retrieved 2022-04-28.

- ^ Malvern, Jack (23 October 2018). "Edgar Allen Poe's horror classic The Tell‑Tale Heart back from the dead after attic clear‑out". The Times. Retrieved 30 November 2018.

- ^ "Poe's Tell-Tale Heart:The Game - Android Apps on Google Play". Play.google.com. Retrieved 2016-01-16.

- ^ Traciy Reyes (12 September 2015). "'The Murder Pact': Lifetime Movie, Also Known As 'Tell-Tale Lies', Airs Tonight Featuring Music By Lindsey Stirling". Inquisitr.com. Retrieved 2016-01-16.

- ^ Ribeiro, Troy (9 August 2018). "'Redrum: A Love Story': A rehash of skewed love stories (IANS Review, Rating: *1/2)". Business Standard. Retrieved 13 April 2020.

- ^ Malvern, Jack (23 October 2018). "Edgar Allen Poe's horror classic The Tell‑Tale Heart back from the dead after attic clear‑out". The Times.

- ^ DeMichiei, Lauren (10 June 2022). "That's a wrap! Post production begins on Poe Movies' Tell-Tale Heart". Orionvega Media. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

- ^ Axelrod, Joshua (26 September 2022). "Poe comes to life with locally shot version of 'The Tell-Tale Heart'". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. Retrieved 17 October 2022.

External links

[edit]- "The Poe Museum"– Full text of "The Tell-Tale Heart"

- "The Tell-Tale Heart"– Full text of the first printing, from the Pioneer, 1843

- Mid-20th century radio adaptations of "The Tell-Tale Heart"

- "The Tell-Tale Heart" study guide and teaching guide– themes, analysis, quotes, teacher resources

- "The Tell-Tale Heart" animation– Award-winning 2010 animated movie, teacher resources, student games

- 20 LibriVox audiorecordings, read by various readers

- The Pioneer, January, 1843, Boston edition.