Nim Chimpsky

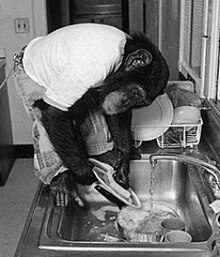

Nim Chimpsky in 1999. Photo by Bob Ingersoll | |

| Species | Chimpanzee |

|---|---|

| Sex | Male |

| Born | November 19, 1973 |

| Died | March 10, 2000 (aged 26) |

| Cause of death | Heart attack |

| Named after | Noam Chomsky |

Neam "Nim" Chimpsky[1] (November 19, 1973 – March 10, 2000) was a chimpanzee used in a study to determine whether chimps could learn a human language, American Sign Language (ASL). The project was led by Herbert S. Terrace of Columbia University with linguistic analysis by psycholinguist Thomas Bever. Chimpsky was named as a pun on linguist Noam Chomsky, who posited that humans are "wired" to develop language.[2]

Over the course of Project Nim, the infant chimp was shuttled between locations and a revolving group of roughly 60 caregivers, including teenagers and grad students, few of whom were proficient in sign language.[3][4][5] Four years into the project, Nim became too difficult to manage and was returned to the Institute for Primate Studies in Oklahoma.[6]

After reviewing the results, Terrace concluded that Nim mimicked signs from his teachers in order to get a reward. Terrace argued that Nim did not initiate conversation or create sentences. Terrace said that he had not noticed this throughout the duration of the study but only upon reviewing video tape.[7][8][1] Terrace ultimately became a popularly cited critic of ape language studies.[9]

Project Nim

[edit]Herbert Terrace, a professory of Psychology at Columbia University, launched Project Nim in 1973, six years after R. Allen and Beatrix Gardner began testing a chimpanzee's ability to acquire American Sign Language with Project Washoe. Terrace named the infant chimpanzee as a pun on Noam Chomsky. With this project, Terrace intended to challenge Chomsky's assertion that only humans can use language.[10] (Terrace's mentor, B.F. Skinner, a key figure in behaviorism, was known as an academic target and rival of Chomsky.[11])

Nim's early years

[edit]

Nim's life history is detailed in Elizabeth Hess's seminal biography, Nim Chimpsky: The Chimp Who Would Be Human (2008), which became the basis for a 2011 documentary film directed by James Marsh, Project Nim (see below).

Nim was born at the Institute for Primate Studies in Norman, Oklahoma. A few days after his birth, he was taken from his sedated mother and placed in the New York City home of Stephanie LaFarge. LaFarge was a former grad student of Terrace's with three children and four stepchildren.[12] LaFarge "knew nothing" about chimps and instantly recognized that the arrangement would be a problem.[13] The LaFarge household was unconventional: she breastfed the chimp (though she had no milk)[13][14] and smoked pot with him.[13][15] Stephanie LaFarge and her daughter Jennie Lee used signs sporadically, focusing instead on play and establishing trust, which they saw as a developmental need. They did not maintain records of Nim's development and did not support the harsh discipline practices that Terrace and his lead trainer at the time demanded. (This included the use of cattle prods[16] and forcing Nim into a small, dark box when he misbehaved.[17]). By mutual agreement two years later, Nim was moved out of the LaFarge brownstone and into a large house in Riverdale, where a grad student, Laura-Ann Petitto, took over as primary caregiver.

After the move to Riverdale, Nim exhibited symptoms of intense anxiety. For the first few weeks, he refused to be alone for even a minute.[18] When left with a new person, he would rip off his clothes and pee and poop all over the room.[19] His habit of "sinking his teeth into human flesh" -- which started before he was a year old -- became both more frequent and more damaging.[20]

Adding further complication, Terrace became romantically involved with Petitto. (He had also been sexually involved with LaFarge but the relationship ended years before Project Nim.) After he "abruptly" ended the relationship, Petitto quit,[6] cutting off Nim (again) from his closet companion and maternal figure. Terrace's two other full-timers quit around the same time.[21] In the wake of these turnovers, Nim's behavior deteriorated further; he became more aggressive and less compliant with sign-language sessions.[13]

Problems with the study

[edit]A number of factors were problematic in the study of Nim’s signing abilities, including the definition of language, turnover of staff, varying teaching methods, and the traumas inflicted upon Nim. For any such psychological study to be considered ethical, participants must to be able to consent, which the chimpanzee could not. [22]

Another problem with the study was the quality (and number) of people working with Nim. There were about 60 total, mostly volunteers, and few were proficient in sign language.[23] Mary Wambaugh, a deaf woman fluent in ASL, joined the team three years into the study and raised concerns that the others were improperly signing. She told Terrace that Nim was being taught a pidgin version of the language, not proper ASL, which has a structure and set of rules. As Hess, observed, this made sense given the study's heavy reliance on students and untrained volunteers. The caregivers signed word-by-word, the same way Nim did.[24]

Another significant problem involved Nim's classroom. Nim performed his signs most fluidly and creatively when playing with his (human) friends at "home" — "home" being initially the LaFarge brownstone[25] and, later, the Riverdale mansion.[26] Yet Terrace needed Nim to work primarily in a space at Columbia, a windowless, noisy, 15' square "dungeon."[6] Terrace described the challenges with the space in Nim:

In the classroom, the slightest noise would make Nim jump into the arms of a teacher. At times, he was so scared he tried to hide under his teacher's skirt. The squeals of rats [in a nearby room] caused him to panic. And he would rock back-and-forth on the floor.[27]

Joyce Butler, who took over as primary caregiver after Petitto quit, said that Nim was nearly impossible to wrangle in the classroom and would repeatedly ask to leave by signing "dirty" to go to the bathroom. Butler and her fellow caregivers fought Terrace over his requirement that Nim attend the classroom daily. Eventually, they refused to take him there.

As difficulties with staff, funding concerns, and Nim's behavior came to a head, Terrace called an end to the study. Over intense resistance from staff, he sent Nim back to the Institute for Primate Studies in 1977[6] and then set about analyzing his data.

Terrace's conclusions

[edit]While Nim was in New York, Terrace believed he was learning sign language. But in reviewing the data, Terrace came to a conclusion that surprised most everyone involved: Nim, he said, was not using language at all.[28] Terrace said that he changed his mind when watching videotapes of Nim (in his classroom). Language requires the use of sentences, and Nim didn't use sentences. Though Nim recognized and used signs, Terrace said he did not initiate conversation. When Nim combined signs, they tended to be highly repetitive and filled with "wild cards" -- words like ME, HUG, NIM, and MORE.[29] For example, Nim's longest utterance, 16 signs, was: "Give orange me give eat orange me eat orange give me eat orange give me you."[30] The videotapes, Terrace argued, proved that Nim mimicked his teachers and used signs strictly to get a reward, not unlike a dog or horse.[1][7][8]

Terrace's results shocked some of Nim's trainers and contradicted his earlier observations, including those in his book Nim (1979). That said, his findings regarding the Nim data were generally accepted as accurate. Among the many problems with Terrace's project (see above), he did not build in blind controls, making Project Nim vulnerable to the Clever Hans effect.

Controversy erupted over the fact that Terrace did not restrict his analysis to Nim. He claimed that other apes in other sign language research projects—most notably, Washoe and gorilla Koko—were mere mimmicks as well. He made these claims after examining brief video clips of the apes taken from a NOVA documentary[31] and a film by Allen and Beatrix Gardner.[32] Terrace's criticisms of other ape research led to heated debates, with many scholars contesting Terrace's claims. The arguments back-and-forth were summarized at that time by Jean Marx in Science (1980) and Dava Sobel (1979) and Eugene Linden[33] in the New York Times.

Terrace ultimately became a popularly cited critic of ape language studies.[9]

Life after Project Nim

[edit]

Nim's return to the Institute of Primate Studies (IPS) in Oklahoma was by all accounts traumatic. By contemporary standards, IPS was a dreary facility. The apes spent most of their time in relatively small cages with concrete floors. But IPS founder William Lemmon recognized the critical importance of apes' social interactions and connected the cages so that chimps had access to each other. He also provided a better, healthier diet than the standard monkey chow. Compared to many zoos and other research facilities at the time, the IPS chimps fared relatively well.[6]

Nim's celebrity was unique, but many of the IPS chimps had similarly been raised by humans. Like Nim, they were returned to IPS when they started growing up and exhibiting wild behaviors. Also like Nim, they had never met members of their own species before. The switch from a human environment to concrete cages with alien beasts caused intense stress and, in some cases, self-mutilation.

But Nim's depression turned out to be relatively short-lived compared to other new arrivals at IPS.[34] Though terrified of the other chimps at first, Nim made new friends. Also, several students in Roger Fouts' sign language program enjoyed working with Nim and took him out for walks on the grounds. Nim continued to use signs, including STONE SMOKE TIME NOW to request marijuana.[35] One IPS student, Bob Ingersoll, took a particular interest in Nim and advocated for him in the turmoil that was to follow.

In the early 1980s, University of Oklahoma withdrew its support of the IPS. Faced with the loss of funding, William Lemmon arranged to gradually sell off chimps to a New York University (NYU) biomedical lab, LEMSIP. (Roger Fouts, who had been working with several IPS chimps, had suddenly left for a new position in Washington, taking Washoe and Loulis with him.[33]) Beginning in December 1981, IPS started sending chimps to LEMSIP, including many, like Nim, who had been used in sign language research. Staff at LEMSIP began noticing the chimps using ASL to communicate with them, so vet James Mahoney posted signs around the facility to help the staff understand the chimps' gestures.[6]

When Bob Ingersoll found out about the LEMSIP plan, he called his Nim contacts to launch a protest and press campaign. He also contacted Jane Goodall, who wrote a letter to the University of Oklahoma on the chimps' behalf.[36] Henry Herrman, a lawyer who had caught wind of the story in the Boston Globe[37] reached out to Terrace, who had been quoted, to offer his services. His call to Terrace proved to be fortuitous. Other IPS personnel made a few calls that ultimately led to a CBS news story. When CBS News interviewed Terrace, Terrace said he was shocked to hear about the move and, referring to his contact with Herrman, announced that he would be filing a lawsuit to stop it. (According to James Mahoney of LEMSIP, Terrace had known about the move for several months and only acted outraged when the press attention hit.[38])

Though NYU initially ignored the press, the mounting legal threats and negative attention made holding on to the celebrity chimp — Nim — no longer worth it for the university. NYU arranged to send Nim and fellow chimp Ally back to IPS. Nim had been at LEMSIP for less than a month. The other sign language-trained chimps remained at LEMSIP. The press by then had moved on.

In 1983, philanthropist Cleveland Amory stepped in to buy Nim, by now a celebrity, and brought him to his equine sanctuary, Black Beauty Ranch, in Texas. As the only chimpanzee at the Ranch, Nim sank into a deep depression. Nim would gesture to staff but they did not sign back. When Ingersoll came to visit, Nim signed BOB, OUT, KEY.[39] Ingersoll urged Amory to get a companion for Nim but was ignored. Meanwhile, Nim studied the locks on his cage and would periodically escape and run into the manager's house, raid the refrigerator, and sometimes turn on the TV. Once, in the process, he threw the ranch's pet poodle against a wall, killing it.[6]

A year after Nim's arrival, Amory arranged to adopt another chimp, Sally. In her biography of Nim, Hess writes that the chimps became inseparable. Nim taught Sally how to sign DRINK, BANANA and GUM, three of the words he used most frequently at the ranch.[40] He was frequently seen signing SORRY to Sally after they had a squabble.[41] Nim still escaped, but a new manager handled those escapes differently. When Nim and Sally showed up at his house, he would act happy to see them and let them stay until they got bored. By keeping tensions low, he found, the chimps did not need to be darted.[42]

After almost ten years with Nim, Sally died, sending Nim once again into severe distress. After hearing about Sally's death, Ingersoll arranged to help get three new chimp companions for Nim: Kitty, Midge, and Lulu. The chimps thrived as a small group until March 10, 2000, when Nim died suddenly of a heart attack. He was 26 years old, about half his average life expectancy.[6]

In media

[edit]Project Nim, a documentary film by James Marsh about the Nim study, explores the story (and the wealth of archival footage) to consider ethical issues, the emotional experiences of the participants, and the deeper issues the experiment raised. The film is based on Nim Chimpsky, the biography by Elizabeth Hess, and Hess is credited as the writer. This documentary (produced by BBC Films, Red Box Films, and Passion Films) opened the 2011 Sundance Film Festival.[43] The film was released in theaters on July 8, 2011 by Roadside Attractions[44] and on DVD on February 7, 2012.[45]

Terrace wrote an op-ed in response to what he considered a negative portrayal of his Nim project, stating that the filmmakers inaccurately equated his study's negative results with "failure."[46]

References

[edit]Key sources

[edit]- Hess, Elizabeth (2008). Nim Chimpsky: The Chimp Who Would Be Human. New York: Bantam. ISBN 9780553803839.

- Ingersoll, Robert; Scarnà, Antonina Anna (2023). Primatoloogy, Ethics and Trauma: The Oklahoma Chimpanzee Studies. London and New York: Routledge.

- Linden, Eugene (1986). Silent Partners: The Legacy of the Ape Language Experiments. Times Books. ISBN 0-8129-1239-X.

- Marsh, James (2011) Project Nim, documentary film.

- Marx, Jean L. (March 21, 1980) "Ape-Language Controversy Flares Up." Science. Vol. 27. No. 4437, pp. 1330–1333.

- Sobel, Dava. (October 21, 1970) "Researcher Challenges Conclusion That Apes Can Learn Language." The New York Times. p.1.

- Terrace, H. S. (1979). Nim. New York: Knopf.

- Terrace, H. S.; Singer, P. (November 24, 2011). "Can Chimps Converse?: An Exchange". New York Review of Books.

Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c Terrace, Herbert; Petitto, L. A.; Sanders, R. J.; Bever, T. G. (November 23, 1979). "Can an ape create a sentence" (PDF). Science. 206 (4421): 891–902. Bibcode:1979Sci...206..891T. doi:10.1126/science.504995. PMID 504995. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 22, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2011.

However objective analysis of our data, as well as those obtained by other studies, yielded no evidence of an ape's ability to use a grammar.

- ^ Radick, Gregory (2007). The Simian Tongue: The Long Debate about Animal Language. University of Chicago Press. p. 320.

- ^ "The Chimp That Learned Sign Language". NPR.org.

- ^ See chapters 3 and 4 in Hess, E. (2008)

- ^ Marx, J. (1980) p. 1331

- ^ a b c d e f g h Marsh, J. (2011). Project Nim documentary. Metacritic

- ^ a b Terrace, Herbert. "Project Nim — The Untold Story" (PDF). appstate.edu.

- ^ a b Chomsky, Noam (2007–2008). "On the Myth of Ape Language" (e-mail correspondence). Interviewed by Matt Aames Cucchiaro. Retrieved February 13, 2021 – via chomsky.info.

- ^ a b Terrace, Herbert S. (2019). Why Chimpanzees Can't Learn Language and Only Humans Can. Columbia University Press.

- ^ "A chimp named Nim". Independent Reader. Archived from the original on April 13, 2008. Retrieved March 31, 2008.

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) p. 13

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) p. 61 and ch. 3

- ^ a b c d Linden, Eugene (1987). Silent Partners: The Legacy of the Ape Language Experiments. Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0345342348.

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) pp. 77-78

- ^ Hess. E. (2009) p. 80

- ^ Hess, E (2008) p. 102

- ^ Terrace, H.S. (1979) p. 58

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) p. 122

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) p. 125

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) pp. 89-91

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) p. 131

- ^ Ingersoll, R. & Scarnà, A.A. (2023)

- ^ Marx, J. (1980), p. 1331

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) pp. 142-3

- ^ Terrace, H.S. (1979) p. 54

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) p. 145

- ^ Terrace, H.S. (1979) p. 50

- ^ Sobel, D. (1970)

- ^ Sobel, D (1970)

- ^ Terrace, H. S. (1979). "How Nim Chimpsky Changed My Mind". Ziff-Davis Publishing Company.

- ^ NOVA (July 5, 1974). "The First Signs of Washoe". Internet Archive. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ Gardner, A. & B. (1973). "Teaching sign language to the chimpanzee, Washoe". WorldCat. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

- ^ a b Linden, Eugene (December 19, 1982). "Endangered chimps in the lab". The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) p. 212

- ^ "'Project Nim': A Chimp's Very Human, Very Sad Life". NPR.org. NPR. July 20, 2011.

- ^ Linden, E. (1986) p. 157 and Hess, E. (2008) p. 246

- ^ Blake, Andrew (May 27, 1982). "Hard Times for bright chimp". The Boston Globe. Retrieved October 7, 2024.

- ^ Linden, E. (1986) pp. 141, 155-156

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) p. 290

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) p. 300

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) p. 331

- ^ Hess, E. (2008) p. 307

- ^ "Project Nim". sundance.bside.com. Sundance Film Festival. Archived from the original on July 21, 2012.

- ^ Fleming, Mike Jr. (January 27, 2011). "Sundance: Roadside Attractions To Release 'Project Nim'". Deadline Hollywood. Retrieved December 18, 2014.

- ^ "Project Nim". Metacritic.com.

- ^ Terrace, Herbert (August 20, 2011). "Project Nim-the Untold Story". Scientific American. Retrieved October 8, 2024.

See also

[edit]- Alex (parrot)

- Animal language

- Chantek (orangutan)

- Great ape language

- Jennie, a 1994 novel about a chimpanzee living with a family in the 1970s learning sign language

- Kanzi (bonobo)

- Koko (gorilla)

- List of individual apes

- Lucy (chimpanzee)

- Panbanisha (bonobo)

- Washoe (chimpanzee)

External links

[edit]- "'Test' results". ling.ohio-state.edu. Archived from the original on June 25, 2003.

- "Official website for Project Nim documentary". project-nim.com. Archived from the original on January 20, 2011.