Michael Graves

Michael Graves | |

|---|---|

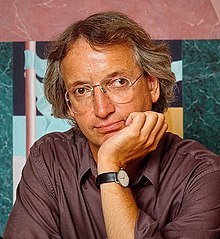

Graves in 1987 | |

| Born | July 9, 1934[1] |

| Died | March 12, 2015 (aged 80)[1] Princeton, New Jersey, U.S.[1] |

| Occupation | Architect |

| Awards | National Medal of Arts (1999)[2] AIA Gold Medal (2001)[2][3] Driehaus Architecture Prize (2012)[4] |

| Buildings | Portland Building (Oregon); Humana Building (Kentucky); Denver Public Library (Colorado); Walt Disney World Swan and Dolphin Resorts (Florida) |

| Website | michaelgraves |

Michael Graves (July 9, 1934 – March 12, 2015) was an American architect, designer, and educator, and principal of Michael Graves and Associates and Michael Graves Design Group. He was a member of The New York Five and the Memphis Group and a professor of architecture at Princeton University for nearly forty years. Following his own partial paralysis in 2003, Graves became an internationally recognized advocate of health care design.

Graves' global portfolio of architectural work ranged from the Ministry of Culture in The Hague, a post office for Celebration, Florida, a prominent expansion of the Denver Public Library to numerous commissions for Disney and the scaffolding design for the 2000 Washington Monument restoration. He was recognized for his influence on architectural movements, including New Urbanism, New Classicism, and postmodernism. His postmodern buildings include the Portland Building in Portland, Oregon and the Humana Building in Louisville, Kentucky.[5]

For his architectural work, Graves received a fellowship of the American Institute of Architects as well as its highest award, the AIA Gold Medal (2001). He was trustee of the American Academy in Rome and was the president of its Society of Fellows from 1980 to 1984. He received the American Prize for Architecture, the National Medal of Arts (1999) and the Driehaus Architecture Prize (2012).

Graves produced both high end and mass consumer product designs for several companies, including Alessi in Italy and Target and J. C. Penney in the United States.[1] The New York Times described Graves as "one of the most prominent and prolific American architects of the latter 20th century, who designed more than 350 buildings around the world but was perhaps best known for [a] teakettle and pepper mill."[6]

Early life and education

[edit]Graves was born on July 9, 1934, in Indianapolis, Indiana, to Erma (née Lowe) and Thomas B. Graves. He grew up in the city's suburbs and later credited his mother for suggesting that he become an engineer or an architect.[1][7]

Graves graduated from Indianapolis's Broad Ripple High School in 1952 and earned a bachelor's degree in architecture in 1958 from the University of Cincinnati.[8][9][10] During college he also became a member of the Sigma Chi fraternity.[11] Graves earned a master's degree in architecture from Harvard University in 1959.[12]

After graduation from college, Graves spent a year working in George Nelson's office. Nelson, a furniture designer and the creative director for Herman Miller, exposed Graves to the work of fellow designers Charles and Ray Eames and Alexander Girard. In 1960 Graves won the American Academy in Rome's Prix de Rome (Rome Prize) and spent the next two years at the academy in Italy.[13][14] Graves describes himself as "transformed" by his experience in Rome: "I discovered new ways of seeing and analyzing both architecture and landscape."[15]

Career

[edit]

Graves began his career in 1962 as a professor of architecture at Princeton University, where he taught for nearly four decades and later helped to establish the Michael Graves College at Kean University in Union Township, New Jersey, and established his own architectural firm in 1964 at Princeton, New Jersey. Graves worked as an architect in public practice designing a variety of buildings that included private residences, university buildings, hotel resorts, hospitals, retail and commercial office buildings, museums, civic buildings, and monuments. During a career that spanned nearly fifty years, Graves and his firm designed more than 350 buildings around the world, and an estimated 2,000 household products.

Princeton University

[edit]In 1962, after two years of studies in Rome, Graves returned to the United States and moved to Princeton, New Jersey, where he accepted a professorship at the Princeton University School of Architecture. Graves taught at Princeton for thirty-nine years while simultaneously practicing architecture. He retired as the Robert Schirmer Professor of Architecture, Emeritus, in 2001.[1][14]

Although Graves was a longtime faculty member at Princeton and trained many of its architecture students, the university did not allow its faculty to practice their profession on its campus. As a result, Graves was never commissioned to design a building for the university.[16] Later in his life he contributed to the founding of a new college,[17][18] which bears his name at Kean University.

Architect

[edit]In his early years as an architect, Graves did designs for home renovation projects in Princeton. In 1964 he founded the architectural firm of Michael Graves & Associate in Princeton and remained in public practice there until the end of his life.[1] His firm maintained offices in Princeton, New Jersey, and in New York City, but his residence in Princeton served as his design studio, home office and library, and a place to display the many objects he collected during his world travels. Nicknamed "The Warehouse", it also displayed many of the household items he designed.[19] After Graves's death, Kean University acquired his former home and studio in Princeton, along with two adjacent buildings.[20]

Modernist

[edit]Graves spent much of the late 1960s and early 1970s designing modernist residences.

His first commission was the Hanselman House in Fort Wayne, Indiana, a design completed in 1971.[21] The modernist structure built for $55,000 received an American Institute of Architects Honor Award in 1975. The New York Times described the home as "another of Graves's experiments in cubist‐influenced spatial manipulations" and cited the obvious influence of Le Corbusier on Graves' work.[22]

Built for friends he met in high school, the home went up for sale in 2017 for $264,888. The four-bedroom residence features a Graves-painted mural in the living room signed by the architect during a visit to the home in 2000.[23]

He also designed the Snyderman House in Fort Wayne (1972, destroyed by fire in 2002) .[24][25]

Graves also became one of the New York Five, along with Peter Eisenman, Charles Gwathmey, John Hejduk and Richard Meier.[26] This informal group of Princeton and New York City architects, also known as the Whites due to the predominant color of their architectural work, espoused a pure form of modernism characterized by clean lines and minimal ornamentation. The New York Five became the "standard-bearers of a movement to elevate modernist architectural form into a serious theoretical pursuit."[26] The book, Five Architects (1973) describes some of their early work.[26]

Postmodernist

[edit]

In the late 1970s, Graves shifted away from modernism to pursue Postmodernism and New Urbanism design for the remainder of his career. He began by sketching designs that had Cubist-inspired elements and strong, saturated colors. Postmodernism allowed Graves to introduce his humanist vision of classicism, as well as his sense of irony and humor. His designs, notable for their "playful style" and "colorful facades," were a "radical departure" from his earlier work.[27] The Plocek Residence (1977), a private home in Warren Township, New Jersey, was among the first of his designs in this new style.[10]

Graves designed some of his most iconic buildings in the early 1980s, including the Portland Building.[10] The fifteen-story Portland Municipal Services Building, his first major public commission, opened in 1982 in downtown Portland, Oregon.[28] The "monolithic cube" with decorated facades and colorful, oversized columns is "considered a seminal Postmodern work"[29] and one of Graves's best-known works of architecture. The celebrated but controversial municipal office also became an icon for the city of Portland and subject to an ongoing preservation debate.[28][5] Regarded as the first major built example of postmodern architecture in a tall office building, the Portland Building was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2011.[30] Although it faced demolition in 2014, the city government decided to proceed with a renovation, estimated to cost $195 million.[28][5]

As a result of the notoriety he received from the Portland Building design, Graves was awarded other major commissions in the 1980s and 1990s. Notable buildings from this period include the Humana Building (1982) in Kentucky and the Newark Museum expansion (1982) in New Jersey.[31] Some architecture critics, including Paul Goldberger of The New York Times, consider the Humana Building, a skyscraper in Louisville, Kentucky, one of Graves's finest building designs. TIME magazine also claimed it was a commercial icon for the city of Louisville and one of the best buildings of the 1980s.[1][28] The San Juan Capistrano Library (1982) in California, another project from this period, shows his interpretation of the Mission Revival style.[32]

Graves and his firm also designed several buildings for the Walt Disney Company in the postmodern style. These include the Team Disney headquarters in Burbank, California;[5] the Dolphin (1987) and Swan (1988) resorts at Walt Disney World in Florida; and Disney's Hotel New York (1989) at Disneyland Paris.[10] Patrick Burke, the project architect for the two resort hotels in Florida, commented that the Walt Disney Company described Graves's designs as "entertainment architecture."[33] In addition to the Swan and Dolphin hotel buildings, Graves's firm designed their original interiors, furnishings, signage, and artwork.[34] Graves's other notable commissions for buildings that were completed in the 1990s include an expansion of the Denver Public Library (1990) and the renovation of the Detroit Institute of Arts (1990).[5]

Postmodern architecture did not have a long-lasting popularity and some of Graves's clients rejected his ideas. For example, his design for an expansion of Marcel Breuer's Whitney Museum of American Art building in New York City in the mid-1980s was highly contested and never built due to architect and local opposition.[1] Graves's designs for a planned Phoenix Municipal Government Center complex were among the project's finalists, but his concept was not selected as the winning entry.[35]

Graves's prominence as a postmodernist architect may have reached its peak during the 1980s and in the early 1990s, but he continued to practice as an architect until his death in 2015. Later works include the O'Reilly Theater (1996) in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; the NCAA Hall of Champions in Indianapolis, Indiana; and 425 Fifth Avenue (2000) in New York City, among others. Graves also received recognition for his multi-year renovation of his personal residence in Princeton.[36] International projects included the Sheraton Miramar Hotel (1997) in El Gouna, Egypt,[37] and the Hard Rock Hotel in Singapore.[37] One of the last projects that Michael Graves and Associates was involved in before Graves's death was the Louwman Museum (2010) in The Hague, Netherlands. Gary Lapera, a principal and studio head of Michael Graves and Associates, designed the museum, also known as the Lowman Collection and the National Automobile Museum of the Netherlands, which houses more than 230 cars.[38]

Product and furniture designer

[edit]

In addition to his architecture, Graves became a noted designer of consumer products. His distinctive style was well known among the general public in the United States in 1980s and 1990s, when he began designing household products for major clients such as the Target Corporation, Alessi, Steuben, and The Walt Disney Company.[1][26] Over the years, the Michael Graves Design Group, a part of his design firm, designed and brought to market more than 2,000 products.[4][39]

In the early 1980s, Ettore Sottsass recruited Graves to become a member of Memphis, a postmodern design group based in Milan, Italy. Graves began designing consumer products such as furniture and home accessories. Especially notable is his "Plaza" dressing table.[4][28][39] Around the same time, Graves became associated with Alessi, a high-end Italian kitchenware manufacturer. Graves designed a sterling silver tea service for Alessi in 1982, a turning point in his career, and he was no longer known solely as an architect. After the $25,000 tea service began to attract buyers, Alberto Alessi commissioned Graves to design a moderate-priced kettle for his company. In 1985 Graves designed his iconic a stainless-steel teakettle (9093 stovetop kettle).[40]

The kettle featured a red, bird-shaped whistle at the end of the spout. It remained the company's top-selling product for fifteen years. In honor of its thirtieth anniversary in 2015, Graves designed a special edition version with a dragon replacing the kettle's bird-shaped whistle.[28][5][41] In Italy in 1987, clock on display Apollodoro Gallery, seventh event The Hour of Architects, with Hans Hollei, Arata Isozaki, Ettore Sottsass, Paolo Portoghesi, paintings by Paolo Salvati, Rome.

In 1997–98, when Graves designed the scaffolding used in the restoration of the Washington Monument in Washington D.C., he met Ron Johnson, a Target executive who appreciated his product designs. (The Target Corporation contributed $6 million toward restoration of the monument.) The result of their acquaintance was the formation of a business relationship between Graves and the U.S. retailer that lasted until 2012.[1][5][42] Graves began the collaboration with Target by designing a half-dozen products for the mass-consumer market. His collection of housewares began selling in Target stores in January 1999.[42][43]

In 1998, Target Corporation commissioned Graves to design a model home to showcase the new line of housewares, but Graves went a step further. He designed "Cedar Gables," contemporary house in Minnetonka, Minnesota, complete with custom furniture, lighting, fixtures, and other unique items, making it only one of three homes he designed and furnished. By 2009, however, Graves noted that the house "doesn't have a wow factor. That gets old quickly."[44] When the partnership with Target ended in 2012, Graves had designed more than 500 objects for the retailer.[45]

Increasingly concerned about Target's dwindling partnerships with outside designers, Graves decided to explore other relationships for marketing his consumer products. After Johnson became CEO of J.C. Penney in 2011, he and Graves reached an agreement for Graves to design products exclusively for Penney's.[42] Graves also created products for other manufacturers. In the 1990s for example, Graves created the Mickey Mouse Gourmet Collection for Moeller Design with the Walt Disney Company's approval. The collection of kitchenware and tabletop items was initially sold through the Walt Disney Company's retail stores and later offered at other retail outlets.[46]

In 2013, Graves designed what became known as the “Hitler teapot” for department store JCPenney, which garnered controversy due to its perceived resemblance to Adolf Hitler.[47]

In addition to housewares, Graves was involved in a variety of other design projects that included sets and costumes for New York City's Joffrey Ballet; a shopping bag for Bloomingdale's department store; jewelry for Cleto Munari of Milan, Italy; vinyl flooring for Tajima, a Japanese company; and rugs for Vorwerk, a German firm. In 1994 Graves opened a small retail store named the Graves Design Store in Princeton, New Jersey, where shoppers could purchase his designs and reproductions of his artwork. At that time Graves had designed products for more than fifty manufacturers.[48]

Later years

[edit]

Graves retired as a professor of architecture at Princeton University in 2001, but remained active in his architecture and design firm. He also became an advocate for the disabled in the last decade of his life. When Graves became paralyzed from the waist down in 2003, the result of a spinal cord infection, the use of a wheelchair heightened his awareness of the needs of the disabled. After weeks of hospitalization and physical therapy, Graves adapted his home to suit his accessibility needs and resumed his architectural and design work.[49][50]

In addition to other types of buildings and household products, Graves designed wheelchairs, hospital furnishings, hospitals, and disabled veteran's housing.[5][49][50] Graves also became a "reluctant health expert," as well as an internationally recognized advocate for accessible design.[5] In 2013, President Barack Obama appointed Graves to an administrative role in the Architectural and Transportation Barriers Compliance Board (also known as the Access Board). The independent agency addresses accessibility concerns for people with disabilities.[51]

In 2014, a year before his death, Graves helped to establish and plan the Michael Graves College, which includes The School of Public Architecture at Kean University in Union Township, New Jersey. Kean University's Bachelor of Arts in Architectural Studies program began in 2015; its Master of Architecture program is slated to begin in 2019. As part of gift from Graves's estate, in 2016 the university acquired The Warehouse at 44 Patton Avenue in Princeton, New Jersey, Graves's former home and studio, and two adjacent buildings. The university plans to use the facility as an educational research center for its School of Public Architecture, although its main campus and its School of Public Architecture are located about forty miles away in Union, New Jersey.[1][20]

Personal life

[edit]Graves' marriage to Gail Devine in 1955 ended in divorce; his subsequent marriage to Lucy James in 1972 also ended in divorce.[52] Graves was the father of three children, two sons and a daughter.[1]

Death

[edit]Graves died at his home in Princeton, New Jersey, on March 12, 2015, at the age of 80, and is buried at Princeton Cemetery.[53]

Legacy

[edit]Graves favored a "humanistic approach to architecture and urban planning"[4] and was a major influence in late-twentieth-century architecture.[54] Graves was among the most prolific and prominent American architects from the mid-1960s to the end of the twentieth century. Graves and his team designed more than 350 buildings in the Postmodern, New Classical, and New Urbanism styles for projects around the world. His architectural designs have been recognized as major influences in all three of these movements.[1][5]

In naming Graves as a recipient of its national design award for lifetime achievement, the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum explained that Graves broadened "the role of the architect in society" and raised "public interest in good design as essential to the quality of everyday life."[4] Graves and his firm designed more than 2,000 consumer products during his lifetime. He was especially noted for his domestic housewares. Many Graves-designed products were sold through mass-market U.S. retailers such as Target and J. C. Penney, but his best-known product is the iconic kettle that he designed in 1985 for Alessi, an Italian housewares manufacturer.[1] As an advocate for the needs of the disabled, Graves used his skills as an architect and designer "to improve healthcare experience for patients, families and clinicians."[4]

Awards and honors

[edit]- In 1979 Graves was elected a Fellow of the American Institute of Architects.[55]

- Graves served as a trustee of the American Academy in Rome and was the president of its Society of Fellows from 1980 to 1984.[56]

- In 1986 Graves received the Golden Plate Award of the American Academy of Achievement.[57]

- In 1994 he was awarded the American Prize for Architecture[55]

- President Bill Clinton awarded Graves the National Medal of Arts in 1999.[2][55]

- Graves was voted GQ's Man of the Year in 1999.[58]

- Graves was awarded the American Institute of Architects' AIA Gold Medal in 2001.[3] His career was also recognized with an AIA Presidential Citation and the Topaz Medallion from the AIA/ACSA.[4]

- Graves was the first recipient of the Michael Graves Lifetime Achievement Award from the AIA-NJ.[4]

- Graves received honorary degrees from the University of Miami in 2001.[59]

- In 2002 the Indiana Historical Society named Graves as an Indiana Living Legend.[60]

- In 2009 Graves was named a Design Futures Council Senior Fellow, one of the twelve honorees selected that year.[61]

- In 2010 Graves was inducted into the New Jersey Hall of Fame.[62]

- The Center for Health Design and Healthcare Design magazine recognized Graves as one of the top twenty-five "most influential people in healthcare design" in 2010.[49]

- Graves was named the Driehaus Architecture Prize in 2012.[4]

- Graves was awarded an honorary degree from Emory University in 2013.[63][64]

- From October 13, 2014, to April 5, 2015, in honor of the fiftieth anniversary of Graves's firm, Michael Graves Architecture and Design, the Grounds for Sculpture in Hamilton, New Jersey, held a retrospective exhibition, "Michael Graves: Past as Prologue."[65]

- On November 22, 2014, the Architectural League of New York held a daylong symposium in his honor at the Parsons School of Design. Several prominent architects such as Steven Holl and Peter Eisenman, as well as Graves served as guests and lecturers.[66]

- In 2015 the Cooper Hewitt Smithsonian Design Museum posthumously awarded Graves a National Design Award for Lifetime Achievement.[4]

Works

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (March 2015) |

- Hanselmann House, Fort Wayne, Indiana, 1968

- Benacerraf House, Princeton, New Jersey, 1969

- Snyderman House, Fort Wayne, Indiana, 1972

- Wageman House, Princeton, New Jersey, 1974

- Fargo-Moorhead Cultural Center Bridge, Fargo, North Dakota, 1977

- Plocek Residence, Warren, New Jersey, 1977 (Graves' first postmodern design)

- Roma Interrotta Exhibition, Rome, Italy, 1978

- Portland Building, Portland, Oregon, 1982

- Humana Building, Louisville, Kentucky, 1982

- Newark Museum expansion, Newark, New Jersey, 1982

- San Juan Capistrano Library, San Juan Capistrano, California, 1982

- Riverbend Music Center, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1984

- Aventine Mixed Use Development, La Jolla, California, 1985

- Crown American Building, Johnstown, Pennsylvania, 1986

- Team Disney headquarters building, Burbank, California, 1986

- Graves Residence ("The Warehouse"), Princeton, New Jersey, 1986

- Shiseido Health Club, Tokyo, Japan, 1986

- Clos Pegase Winery, Calistoga, California, 1987

- Bryan Hall, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia, 1987

- Dolphin Resort, Walt Disney World, Orlando, Florida, 1987

- Swan Resort, Walt Disney World, Orlando, Florida, 1987

- Metropolis master plan, Los Angeles, California, 1988

- Tajima Office Building, Tokyo, Japan, 1988

- Disney's Hotel New York, Euro Disney Resort, now Disneyland Paris, Marne-la-Vallée, France, 1989

- Ten Peachtree Place, Atlanta, Georgia, 1989

- Clark County Library and Theater, Las Vegas, Nevada, 1990

- Dairy Barn renovation, Harbourton, New Jersey, 1990

- Denver Public Library, Denver, Colorado, 1990

- Detroit Institute of Arts master plan, Detroit, Michigan, 1990

- Fukuoka Hyatt Hotel and Office Building, Fukuoka, Japan, 1990

- Kasumi Research and Training Center, Tsukaba, Japan, 1990

- Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics, University of California, Santa Barbara, California, 1990

- Malibu House (private residence), Malibu, California, 1990

- Onjuku Town Hall, Onjuku, Japan, 1990

- Engineering Center, University of Cincinnati College of Engineering, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1990

- Youngstown Historical Center of Industry and Labor, Youngstown, Ohio, 1990

- Arts and Sciences Building, Stockton University, Pomona, New Jersey, 1991

- Thomson Consumer Electronics Americas headquarters, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1992

- U.S. Courthouse renovation, Trenton, New Jersey, 1992

- Astrid Park Plaza Hotel and Business Center, Antwerp, Belgium, 1993

- International Finance Corporation Headquarters of the World Bank, Washington, D.C., 1993

- Michael C. Carlos Museum, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, 1993

- Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport, The Hague, Netherlands, 1993

- Nexus Momochi Residential Tower, Fukuoka, Japan, 1993

- Archdiocesan Center, Newark, New Jersey, 1993

- Rome Reborn Exhibition, Washington, D.C., 1993

- U.S. Post Office, Celebration, Florida, 1993

- 1500 Ocean Drive, Miami Beach, Florida, 1994

- Ocean Steps Retail Center with 1500 Ocean Drive, Miami Beach, Florida, 1994

- One Port Center (Delaware River Port Authority headquarters), Camden, New Jersey, 1994

- Pura-Williams House, Manchester-by-the-Sea, Massachusetts, 1994

- Miramar Resort Hotel, El Gouna, Egypt, 1995

- Topeka & Shawnee County Public Library, Topeka, Kansas, 1995

- The Engineering Research Center, University of Cincinnati, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1995

- Rare Books Library, American Academy, Rome, Italy, 1996

- Charles E. Beatley Jr. Central Library, Alexandria, Virginia, 1996

- House At Indian Hill, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1996

- Indianapolis Art Center, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1996

- Lake Hills Country Club, Seoul, Korea, 1996

- Miele Americas Headquarters, Princeton, New Jersey, 1996

- O'Reilly Theater, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1996

- French Institute⁄Alliance Française Library, New York City, 1997

- De Luwte House, Loenen aan de Vecht, Netherlands, 1997

- North Hall Residence, Drexel University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1997

- El Gouna Golf Club, El Gouna, Egypt, 1997

- El Gouna Golf Hotel, El Gouna, Egypt, 1997

- El Gouna Golf Villas, El Gouna, Egypt, 1997

- Fortis/AG Headquarters, Brussels, Belgium, 1997

- Fukuoka Office Building, Fukuoka, Japan, 1997

- Hyatt Hotel Taba Heights, Taba Heights, Egypt, 1997

- Intercontinental Hotel, Taba Heights, Egypt, 1997

- Laurel Hall, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, New Jersey, 1997

- NCAA Hall of Champions and headquarters, Indianapolis, Indiana, 1997

- U.S. Courthouse, Washington, D.C., 1997

- Bristol/Savoy Towers (Ten Good City), Fukuoka, Japan, 1998

- Cedar Gables House, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 1998

- Impala Building, New York City, 1998

- Castalia Building (Ministry of Public Health), The Hague, Netherlands, 1998

- Saint Martin's College Library, Lacey, Washington, 1998

- Master plan, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, New Jersey, 1999

- Laurel Hall expansion, New Jersey Institute of Technology, Newark, New Jersey, 1999

- Philadelphia Eagles/Novacare Training Center, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 1999

- Pittsburgh Cultural District Service Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, 1999

- Private residence, Harbourton, New Jersey, 1999

- Martel, Brown and Jones Colleges at Rice University, Houston, Texas, 1999

- Singapore National Library Competition, Singapore, 1999

- Target House Fountain, Memphis, Tennessee, 1999

- Washington Monument scaffolding, Washington, D.C., 1999

- Watch Technicum, Lancaster County, Pennsylvania, 1999

- 425 Fifth Avenue, New York City, 2000

- Capital Regional Medical Center, Tallahassee Community Hospital, Tallahassee, Florida, 2000

- Famille Tsukishima Apartment Building, Tokyo, Japan, 2000

- Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas Houston Branch, Houston, Texas, 2000

- Hart Production Studios, San Francisco, California, 2000

- Newark Museum Science Gallery, Newark, New Jersey, 2000

- Perseus Office, Washington, D.C., 2000

- Private residence, Lake Geneva, Switzerland, 2000

- U.S. Embassy Compound (embassy and housing), Seoul, South Korea, 2000

- Children's Theatre Company, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2001

- Fukuoka Office Building, Fukuoka, Japan, 2001

- Kasteel Holterveste, De Haverleij, Netherlands, 2001

- Mahler 4, Amsterdam, Netherlands, 2001

- Michael C. Carlos Museum renovation, Emory University, Atlanta, Georgia, 2001

- Three On The Bund, Shanghai, China, 2001

- Arts Council of Princeton, Princeton, New Jersey, 2002

- U.S. Department of Transportation headquarters, Washington, D.C., 2002

- Kavli Institute for Theoretical Physics/Kohn Hall, University of California, Santa Barbara, California, 2002

- National Museum of Prehistory, Taitung, Taiwan, 2002

- Arts and Science Building, New Jersey City University, Jersey City, New Jersey, 2002

- New Jersey State Police Training Center and headquarters, Trenton, New Jersey, 2002

- Resort master plan, Canary Islands, Spain, 2002

- South Campus master plan, Rice University, Houston, Texas, 2002

- Saint Mary's Catholic Church, Rockledge, Florida, 2002

- Target Club Wedd House contest prize, 2002

- Campus master plan, Florida Institute of Technology Melbourne, Florida, 2003

- Sigma Chi fraternity house, George Washington University, Washington, D.C., 2003

- Housing For Martin House, Trenton, New Jersey, 2003

- The Pinnacle and 260 Main Street, White Plains, New York, 2003

- U.S. Courthouse, Nashville, Tennessee, 2003

- Alter Hall, Fox School of Business, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2004

- Indianapolis Art Center master plan, Indianapolis, Indiana, 2004

- Maxwell Place On The Hudson, Interiors Block A, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2004

- Chancellor Green Interiors, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, 2004

- Riverwalk 2, Nishinippon Institute of Technology Design School, Kitakyushu, Japan, 2004

- Trump International Hotel, Fort Lauderdale, Florida, 2004

- School Of Business, University of Miami, Coral Gables, Florida, 2004

- 701 E. Baltimore, Baltimore, Maryland, 2005

- Azulera Resort Hotel and Residences, Brasilito Bay Guanacaste, Costa Rica, 2005

- Burj Dubai Towers, Dubai, United Arab Emirates, 2005

- The Enclave Residential Condominiums, Puerto Vallarta, Mexico, 2005

- College Of Psychology and Autism, Florida Institute of Technology, Melbourne, Florida, 2005

- Hyatt Hotel, Beirut, Lebanon, 2005

- Luxury Condominium Towers, Beirut, Lebanon, 2005

- Maxwell Place On The Hudson, Interiors Block B, Hoboken, New Jersey, 2005

- Museum of the Shenandoah Valley, Winchester, Virginia, 2005

- Paterson Public Schools complex, Paterson, New Jersey, 2005

- Riverside Park residential development master plan, Fairfax County, Virginia, 2005

- Springhill Lake master plan, Greenbelt, Maryland, 2005

- Storehouse prototype retail store, West Palm Beach, Florida, 2005

- Allegria Residence, 6th of October City, Egypt, 2006

- The Falls at Lake Travis community master plan, Austin, Texas, 2006

- Four Seasons Residence at Town Lake, Austin, Texas, 2006

- Minneapolis Institute of Arts expansion, Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2006

- Notre Dame Club, University of Notre Dame, South Bend, Indiana, 2006

- Private residence, Sentosa, Singapore, 2006

- St. Regis Hotels & Resorts Cairo, Cairo, Egypt, 2006

- Shake-a-Leg Residences, Miami, Florida, 2006

- Saint Coletta of Greater Washington, Washington, D.C., 2006

- Wyndham Hotel prototypes, 2006

- School of Nursing, Columbia University, New York City, 2007

- Community master plan, New Cairo, Egypt, 2007

- Detroit Institute of Arts major renovation and expansion, Detroit, Michigan, 2007

- MarketFair Retail Center, Princeton, New Jersey, 2007

- Equestrian City Tower, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, 2008

- Paul Robeson Center for the Arts, Arts Council of Princeton, Princeton, New Jersey, 2008

- Mitchell Institute for Fundamental Physics and Astronomy and Department of Physics Building, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas, 2009[67][68]

- Alter Hall, Fox School of Business, Temple University, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, 2009

- Wu-Wilcox Halls additions and interiors, Princeton University, Princeton, New Jersey, 2006

- Resorts World at Sentosa, Singapore, 2010[69]

- Louwman Museum (National Automobile Museum), The Hague, Netherlands, 2010

- PS/IS 42, Arverne, New York, 2012

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Robin Pogrebin (March 13, 2015). "Michael Graves, Who Put Big Ideas Into Small Items" (obituary). The New York Times, Late Edition (East Coast). p. A1. See also:Robin Pogrebin (March 13, 2015). "Michael Graves, 80, Dies; Postmodernist Designed Towers and Teakettles". The New York Times. East Coast Edition: A1. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ a b c Iovine, Julie V. (2000). Michael Graves. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 95. ISBN 0-8118-3251-1.

- ^ a b Robin Groom (January 28, 2001). "Datebook". The Washington Post. p. F3. Archived from the original on March 8, 2021. Retrieved December 22, 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Phil Patton (May 5, 2015). "Michael Graves Awarded National Design Award for Lifetime Achievement". DesignApplause. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hawthorne, Christopher (March 12, 2015). "Michael Graves dies at 80; pioneering figure in postmodern architecture". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ^ Robin Pogrebin (March 12, 2015). "Michael Graves, 80, Dies; Postmodernist Designed Towers and Teakettles". New York Times.

- ^ Julie V. Iovine (2000). Michael Graves. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. p. 8. ISBN 0-8118-3251-1.

- ^ "Riparian, 1952". Indianapolis Public Library Digital Collections. Retrieved March 27, 2023.

- ^ Iovine, p. 94.

- ^ a b c d "Michael Graves". Biography.com. Archived from the original on April 25, 2017. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ "Michael Graves – Sigma Chi". Retrieved December 11, 2024.

- ^ "Michael Graves". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved March 12, 2015.

- ^ Iovine, Michael Graves, p. 15; Toby Israel (2003). Some Places Like Home: Using Design Psychology to Create Ideal Places. New York: Wiley-Academy. p. 26. ISBN 0470849509.

- ^ a b Michael Graves (September 2, 2012). "Drawing with a Purpose". The New York Times. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ "Introduction" in Brian M. Ambroziak (2016). Michael Graves: Images of a Grand Tour. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 978-1616894733.

- ^ Israel, p. 126.

- ^ "Kean University creates Michael Graves School of Architecture". Building Design + Construction. October 28, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ "Michael Graves School of Architecture to Open in 2015". ArchDaily. October 30, 2014. Retrieved March 3, 2021.

- ^ Built in the 1920s by Italian masons who came to work on buildings at Princeton University, the warehouse originally stored furniture. Graves bought the dilapidated building in 1970 for $30,000. He remodeled and expanded the L-shaped structure into a Tuscan-style villa. Graves later added a terracotta-colored surface to its exterior later. See Iovine, p. 18, and Patricia Leigh Brown (November 3, 1996). "Architect Michael Graves get busloads of visitors". Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana.

- ^ a b Dan Howarth (July 6, 2016). "Michael Graves' Princeton Home to Become Architecture Education Centre". Dezeen. Retrieved June 12, 2017. Also: "Michael Graves College: School of Public Architecture". Kean University. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ Ayoubi, Ayda (July 14, 2017). "Architect Michael Graves' First Commission Hits the Market". Architect Magazine.

- ^ Goldberger, Paul (May 18, 1975). "Design: The national A.I.A. awards". The New York Times.

- ^ Hansen, Kristine (July 18, 2017). "Michael Graves-Designed Modern Home Is a Steal in Fort Wayne". Realtor.com.

- ^ Cindy Larson (May 14, 2011). "Live Inside a Work of Art". News-Sentinel. Fort Wayne, Indiana. Archived from the original on March 13, 2014. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ Dan Howarth (May 21, 2017). "Five Mid-Century Gems in Unlikely Architecture Haven Fort Wayne". Dezeen. Retrieved June 12, 2017.

- ^ a b c d Paul Goldberger (February 11, 1996), "Architecture View: A Little Book That Led Five Men to Fame", The New York Times, retrieved August 22, 2017

- ^ Israel, p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f Allan G. Brake (September 12, 2015). "Postmodern architecture: the Portland Municipal Services Building, Oregon, by Michael Graves". Dezeen. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Marcus Fairs (March 12, 2015). "Michael Graves dies aged 80". Dezeen. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ "Portland Building gets a place on national history list". Portland Tribune. November 17, 2011. Retrieved July 6, 2013.

- ^ Israel, p. 128; Iovine, p. 11.

- ^ Aaron Betsky (January 9, 2013). "Beyond Buildings: Michael Graves's San Juan Capistrano Library, 30 Years Later". Architect. American Institute of Architects. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Dan Howarth (April 28, 2017). "Postmodern Architecture: Walt Disney World Dolphin and Swan Hotels by Michael Graves". Dezeen. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ Iovine, pp. 12–13.

- ^ "Phoenix Municipal Government Center Design Competition Collection–Design and the Arts Library". Arizona State University Library. Retrieved November 14, 2017.

- ^ "Dwell Takes a Look Inside Michael Graves' Princeton Home". Curbed National. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ a b "Michael Graves: Legendary Advocate of Postmodernism and Household Designer". Coffee Break. Arch20.com. Retrieved February 5, 2018.

- ^ Catherine Warmann (November 17, 2010). "The Louwman Museum by Michael Graves and Associates". Dezeen. Retrieved August 23, 2017.

- ^ a b Iovine, p. 94–95.

- ^ Iovine, pp. 14–16.

- ^ Dan Howarth (August 25, 2015). "Alessi celebrates Michael Graves' 9093 kettle anniversary with dragon-shaped whistle". Dezeen. Retrieved August 23, 2017. Also: "Alessi". Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ a b c "Designer Michael Graves on Moving to J.C. Penney". Bloomberg.com. March 29, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2015.

- ^ Iovine, p. 21. Also: Michael Pogrebin (March 15, 2015). "A Pioneer of Postmodern Design, Big and Small". Toronto Star. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ Lynn Underwood (September 2, 2009). "Gables by GRAVES". Star Tribune. Retrieved May 16, 2016.

- ^ Iovine, p. 21.

- ^ Abe Amidor (September 15, 1994). "Mouse in the House". Indianapolis Star. Indianapolis, Indiana: C1–2.

- ^ Chappell, Bill (May 29, 2013). "Tempest Over A Teapot: JC Penney Removes 'Hitler' Billboard". NPR. Retrieved March 24, 2022.

- ^ Iovine, pp. 16, 20.

- ^ a b c "Dwell Takes a Look Inside Michael Graves' Princeton Home". Curbed National. Archived from the original on May 2, 2012. Retrieved March 16, 2015. See also: Healthcare Design December 2010; 10 (12):26–29.

- ^ a b Julie V. Iovine (June 12, 2003). "An Architect's World Turned Upside Down". New York Times. Retrieved March 13, 2015.

- ^ Amy Frearson (February 5, 2013). "Barack Obama appoints Michael Graves to advise on accessible design". Dezeen. Retrieved June 9, 2017.

- ^ Israel, p. 69; "Michael Graves Biography". IMDb. Retrieved January 5, 2018.

- ^ Robin Pogrebin (March 12, 2015). "Michael Graves, Postmodernist Architect Who Designed Towers and Teakettles, Dies at 80". The New York Times. Retrieved March 14, 2015.

- ^ Israel, p. 11.

- ^ a b c Snow, Shauna (September 22, 1999). "Morning Report". Los Angeles Times. p. 2.

- ^ "Society of Fellows: Michael Graves, FAR 1962, RAAR 1978". American Academy in Rome. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 7, 2017.

- ^ "Golden Plate Awardees of the American Academy of Achievement". www.achievement.org. American Academy of Achievement.

- ^ Iovine, p. 7.

- ^ "UM History and Commencement Honorary Degree Recipients". University of Miami. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

- ^ "Living Legends". The Bridge. 8 (3). Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society: 4. May 2002.

- ^ "Senior Fellows". di.net. Archived from the original on November 6, 2007. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ "City News: Greater New York Watch". Wall Street Journal, Eastern Edition. May 3, 2010. p. A27.

- ^ "Honorary Degrees: Recent Recipients". emory.edu. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ "Rita Dove to Deliver Emory Commencement Speech and Receive Two Honorary Degrees from Emerson College and Emory University". virginia.edu. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ "Exhibitions". Grounds For Sculpture. Archived from the original on March 16, 2015. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ Fred A. Bernstein. "The Mouse That Roared". construction.com. Retrieved March 16, 2015.

- ^ "Mitchell Institute Texas A&M University". Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ "Tour Mitchell Physics". Archived from the original on March 5, 2016. Retrieved February 20, 2016.

- ^ Zachariah, Natasha Ann. "American architect Michael Graves who masterplanned Resorts World Sentosa dies". Straits Times. Retrieved December 5, 2015.

Further reading

[edit]- Volner, Ian (2017). Michael Graves: Design for Life. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 9781616895631.

- Ambroziak, Brian M. (2016). Michael Graves: Images of a Grand Tour. Princeton Architectural Press. ISBN 9781616894733. (reprint edition)

- Tischler Linda (August 2004). "A Design for Living". Fast Company. Retrieved August 24, 2017.

External links

[edit]- Michael Graves buildings

- 1934 births

- 2015 deaths

- 20th-century American architects

- 21st-century American architects

- American industrial designers

- Architects from Indianapolis

- Burials at Princeton Cemetery

- Dinnerware designers

- Driehaus Architecture Prize winners

- Fellows of the American Institute of Architects

- Harvard Graduate School of Design alumni

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- New Classical architects

- Postmodern architects

- Princeton University faculty

- Recipients of the AIA Gold Medal

- United States National Medal of Arts recipients

- University of Cincinnati alumni

- Product designers