Nanjing Massacre

| Nanjing Massacre | |

|---|---|

| Part of the Battle of Nanking | |

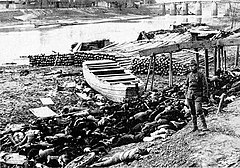

A Japanese soldier pictured with the corpses of Chinese civilians by the Qinhuai River | |

| Location | Nanjing, Jiangsu, China |

| Coordinates | 32°2′15″N 118°44′15″E / 32.03750°N 118.73750°E |

| Date | From December 13, 1937, for six weeks[a] |

| Target | Chinese people |

Attack type | Mass murder, wartime rape, looting, torture, arson |

| Deaths | 200,000 civilians (consensus),[1] estimates range from 40,000 to over 300,000 |

| Victims | 20,000 to 80,000 women and children raped, 30,000 to 40,000 POWs executed (another 20,000 male civilians falsely accused of being soldiers executed) |

| Perpetrators | Imperial Japanese Army

|

| Motive | |

| This article is part of the series on the |

| Nanjing Massacre |

|---|

| Japanese war crimes |

| Historiography of the Nanjing Massacre |

| Films |

| Books |

| History of the Republic of China |

|---|

|

|

|

The Nanjing Massacre[b] or the Rape of Nanjing (formerly romanized as Nanking[c]) was the mass murder of Chinese civilians by the Imperial Japanese Army in Nanjing, the capital of the Republic of China, immediately after the Battle of Nanking and retreat of the National Revolutionary Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War.[2][3][4][5] The massacre took place over a period of six weeks beginning on December 13, 1937.[a] Estimates of the death toll vary from a low of 40,000 to a high of over 300,000, and estimates of rapes range from 20,000 to over 80,000. Most scholars support the validity of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, which estimated that at least 200,000 were killed. Other crimes included torture, looting, and arson. The massacre is considered one of the worst wartime atrocities in history.[7][8][9] In addition to civilians, numerous POWs and men who looked of military-age were indiscriminately slaughtered.

After the outbreak of the war in July 1937, the Japanese had pushed quickly through China after capturing Shanghai in November. As the Japanese marched on Nanjing, they committed violent atrocities in a terror campaign, including killing contests and massacring entire villages.[10] By early December, the Japanese Central China Area Army under the command of General Iwane Matsui reached the outskirts of the city. The Chinese army withdrew the bulk of its forces since Nanjing was not a defensible position. The civilian government also fled, leaving the city under the de facto control of German citizen John Rabe, who created the Nanking Safety Zone in an attempt to protect its civilians. Prince Yasuhiko Asaka was installed as temporary commander in the campaign, and he issued an order to "kill all captives". Iwane and Asaka took no action to stop the massacre after it began.

The massacre began on December 13 after Japanese troops entered the city after days of intense fighting and continued to rampage through it unchecked. Thousands of captured Chinese soldiers were summarily executed en masse in violation of the laws of war, as were male civilians falsely accused of being soldiers. Widespread rape of female civilians took place, their ages ranging from infants to the elderly, and one third of the city was destroyed by arson. Rabe's Safety Zone was mostly a success, and is credited with saving at least 200,000 lives. After the war, Matsui and several other commanders at Nanking were found guilty of war crimes and executed. Some other Japanese military leaders in charge at the time of the Nanjing Massacre were not tried only because by the time of the tribunals they had either already been killed or committed ritual suicide. Asaka was granted immunity as a member of the imperial family and never tried.

The massacre remains a wedge issue in Sino-Japanese relations, as Japanese nationalists and historical revisionists, including top government officials, have either denied or minimized the massacre.

Military situation

The Second Sino-Japanese War commenced on July 7, 1937, following the Marco Polo Bridge incident, and rapidly escalated into a full-scale war in northern China between the Chinese and Japanese armies.[11] The National Revolutionary Army, however, wanted to avoid a decisive conflict in the northern region and instead opened a second front by launching offensives against Japanese forces in Shanghai.[11] In response, Japan deployed an army led by General Iwane Matsui, to fight the Chinese forces in Shanghai.[12]

In August 1937, the Japanese army invaded Shanghai, where they met strong resistance and suffered heavy casualties. The battle was bloody as both sides faced attrition in urban hand-to-hand combat.[13] Although the Japanese forces succeeded in forcing the Chinese forces into retreat, the General Staff Headquarters in Tokyo initially decided not to expand the war because they wanted the war to end.[14] However, there was a significant disagreement between the Japanese government and its army in China.[15] Matsui had expressed his intention to advance on Nanjing even before departing for Shanghai. He firmly believed that capturing Nanjing, the Chinese capital, would lead to the collapse of the entire Nationalist Government of China, thereby securing a swift and decisive victory for Japan.[14][15] The General Staff Headquarters in Tokyo eventually relented to the demands of the Imperial Japanese Army in China by approving the operation to attack and capture Nanjing.[16]

Strategy for the defense of Nanjing

In a press release to foreign reporters, Tang Shengzhi announced the city would not surrender and would fight to the death. Tang gathered a garrison force of some 81,500 soldiers,[17] many of whom were untrained conscripts, or troops exhausted from the Battle of Shanghai. The Chinese government left for relocation on December 1, and the president left on December 7, leaving the administration of Nanjing to an International Committee led by John Rabe, a German national and Nazi Party member.

In an attempt to secure permission for this cease-fire from Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, Rabe, who was living in Nanjing and had been acting as the Chairman of the Nanking International Safety Zone Committee, boarded the USS Panay (PR-5) on December 9. From this gunboat, Rabe sent two telegrams. The first was to Chiang through an American ambassador in Hankow, asking that Chinese forces "undertake no military operations" within Nanjing. The second telegram was sent through Shanghai to Japanese military leaders, advocating for a three-day ceasefire so that the Chinese could withdraw from the city.

The following day, on December 10, Rabe got his answer from the Generalissimo. The American ambassador in Hankow replied that although he supported Rabe's proposal for a ceasefire, Chiang did not. Rabe says that the ambassador also "sent us a separate confidential telegram telling us that he has been officially informed by the Foreign Ministry in Hankow that our understanding that General Tang agreed to a three-day armistice and the withdrawal of his troops from Nanjing is mistaken, and moreover that Chiang Kai-shek has announced that he is not in a position to accept such an offer." This rejection of the committee's ceasefire plan, in Rabe's mind, sealed the fate of the city. Nanjing had been constantly bombed for days, causing massive destruction and civilian casualties.

On December 11, Rabe found that Chinese soldiers were still residing in areas of the Safety Zone, meaning that it became an intended target for Japanese attacks despite the majority being innocent civilians. Rabe commented on how efforts to remove these Chinese troops failed and Japanese soldiers began to lob grenades into the refugee zone.[18]

Approach of the Imperial Japanese Army

Japanese war crimes on the march to Nanjing

Although the massacre is generally described as having occurred over a six-week period after the fall of Nanjing, the crimes committed by the Japanese army were not limited to that period. Numerous atrocities were committed as the Japanese army advanced from Shanghai to Nanjing, including rape, torture, arson and murder.

The 170 miles between Shanghai and Nanjing were transformed into "a nightmarish zone of death and destruction."[10] Japanese planes frequently strafed unarmed farmers and refugees "for fun."[20] Civilians were subjected to extreme violence and brutality in a foreshadowing of the upcoming Massacre. For example, the Nanqiantou hamlet was set on fire, with many of its inhabitants locked within the burning houses. Two women, one of them pregnant, were raped repeatedly. Afterwards, the soldiers "cut open the belly of the pregnant woman and gouged out the fetus." A crying two-year-old boy was wrestled from his mother's arms and thrown into the flames, while the mother and remaining villagers were bayoneted and thrown into a creek.[21][10]

In addition, Jiading was shelled by Japanese forces, then 8,000 of its civilian residents indiscriminately murdered. Half of Taicang was razed to the ground, and the salt and grain stores looted.[22] Chinese civilians often committed suicide, such as two girls who deliberately drowned themselves near Pinghu, an event witnessed by Japanese First Lieutenant Nishizawa Benkichi.[23]

According to Kurosu Tadanobu of the 13th division:[24]

“We'd take all the men behind the houses and kill them with bayonets and knives. Then we'd lock up the women and children in a single house and rape them at night... Then, before we left the next morning, we'd kill all the women and children, and to top it off, we'd set fire to the houses, so that even if anyone came back, they wouldn't have a place to live.”

According to one Japanese journalist embedded with Imperial forces at the time:[25]

The reason that the [10th Army] is advancing to Nanjing quite rapidly is due to the tacit consent among the officers and men that they could loot and rape as they wish.

In his novel Ikiteiru Heitai ('Living Soldiers'), Tatsuzō Ishikawa vividly describes how the 16th Division of the Shanghai Expeditionary Force committed atrocities on the march between Shanghai and Nanjing. The novel itself was based on interviews that Ishikawa conducted with troops in Nanjing in January 1938.[26]

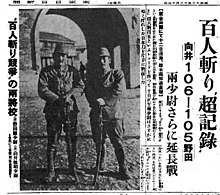

Perhaps the most notorious atrocity was a killing contest between two Japanese officers as reported in the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun and the English-language Japan Advertiser. The contest—a race between the two officers to see who could kill 100 people first using only a sword—was covered much like a sporting event with regular updates on the score over a series of days.[27][28] In Japan, the veracity of the newspaper article about the contest was the subject of ferocious debate for several decades starting in 1967.[29]

In 2000, historian Bob Tadashi Wakabayashi concurred with certain Japanese scholars who had argued that the contest was a concocted story by the Japanese, with the collusion of the soldiers themselves for the purpose of raising the national fighting spirit.[30]

In 2005, a Tokyo district judge dismissed a suit by the families of the lieutenants, stating that "the lieutenants admitted the fact that they raced to kill 100 people" and that the story cannot be proven to be clearly false.[31] The judge also ruled against the civil claim of the plaintiffs because the original article was more than 60 years old.[32] The historicity of the event remains disputed in Japan.[33]

Chinese scorched-earth policy

The Nanjing garrison force set fire to buildings and houses in the areas close to Xiaguan to the north as well as in the environs of the eastern and southern city gates. Targets within and outside of the city walls—such as military barracks, private homes, the Ministry of Communication, forests, and entire villages—were completely burnt down, at an estimated value of US$20–30 million (1937).[34][35][36]

Establishment of the Nanking Safety Zone

Many Westerners were living in the city at that time, conducting trade or on missionary trips. As the Japanese army approached Nanjing, most of them fled the city, leaving 27 foreigners. Five of these were journalists who remained in the city a few days after it was captured, leaving the city on December 16. Fifteen of the remaining 22 foreigners formed a committee, called the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone in the western quarter of the city.[37]

German businessman John Rabe was elected as its leader, in part because of his status as a member of the Nazi Party and the existence of the German-Japanese bilateral Anti-Comintern Pact. The Japanese government had previously agreed not to attack parts of the city that did not contain Chinese military forces, and the members of the Committee managed to persuade the Chinese government to move their troops out of the area. The Nanking Safety Zone was demarcated through the use of Red Cross Flags.[38]

On December 1, 1937, Nanjing Mayor Ma Chaochun ordered all Chinese citizens remaining in Nanjing to move into the Safety Zone. Many fled the city on December 7, and the International Committee took over as the de facto government of Nanjing.

Minnie Vautrin was a Christian missionary who established Ginling Girls College in Nanking, which was within the established Safety Zone. During the massacre, she worked tirelessly in welcoming thousands of female refugees to stay in the college campus, sheltering up to 10,000 women.[39]

Establishment of refugee camp at cement factory

At the age of 26, a Dane named Bernhard Arp Sindberg began his role as a guard at a cement factory in Nanjing in December 1937, days before the Japanese invasion of Nanjing.[40] As the massacre began, Sindberg and Karl Gunther, a German colleague, converted the cement factory into a makeshift refugee camp where they offered refuge and medical assistance to approximately 6,000 to 10,000 Chinese civilians.[41][42]

Knowing that Imperial Japan was not hostile towards Denmark or Nazi Germany, thus showing respect for their flags, Sindberg painted a large Danish flag on the cement factory roof to deter the Japanese army from bombing the factory.[41] To keep Japanese troops away from the factory, he and Gunther strategically placed the Danish flag and the German swastika around the site.[41] Whenever the Japanese approached the gate, Sindberg would display the Danish flag and step out to converse with them, and eventually, they would leave.[40]

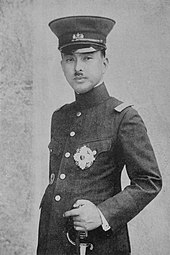

Prince Asaka appointed as commander

In a memorandum for the palace rolls, Hirohito singled Prince Yasuhiko Asaka out for censure as the one imperial kinsman whose attitude was "not good." He assigned Asaka to Nanjing as an opportunity to make amends.[43]

On December 5, Asaka left Tokyo by plane and arrived at the front three days later. He met with division commanders, lieutenant-generals Kesago Nakajima and Heisuke Yanagawa, who informed him that the Japanese troops had almost completely surrounded 300,000 Chinese troops in the vicinity of Nanjing and that preliminary negotiations suggested that the Chinese were ready to surrender.[44]

Prince Asaka issued an order to "kill all captives," thus providing official sanction for the crimes which took place during and after the battle.[45] Some authors record that Prince Asaka signed the order for Japanese soldiers in Nanjing to "kill all captives".[46] Others assert that lieutenant colonel Isamu Chō, Asaka's aide-de-camp, sent this order under the Prince's sign-manual without the Prince's knowledge or assent.[47] Nevertheless, even if Chō took the initiative, Asaka was nominally the officer in charge and gave no orders to stop the carnage. While the extent of Prince Asaka's responsibility for the massacre remains a matter of debate, the ultimate sanction for the massacre and the crimes committed during the invasion of China were issued in Emperor Hirohito's ratification of the Japanese army's proposition to remove the constraints of international law on the treatment of Chinese prisoners on August 5, 1937.[48]

Battle of Nanjing

Siege of the city

The Japanese military continued to move forward, breaching several lines of Chinese resistance, and arrived outside the city gates of Nanjing on December 9.

Demand for surrender

In the meantime, members of the Committee contacted Tang and proposed a plan for three-day cease-fire, during which the Chinese troops could withdraw without fighting while the Japanese troops would stay in their present position.

John Rabe boarded the U.S. gunboat Panay on December 9 and sent two telegrams, one to Chiang Kai-shek by way of the American ambassador in Hankow (Hankou), and one to the Japanese military authority in Shanghai.

Assault and capture of Nanjing

Despite resisting the assault fiercely, the Chinese defenders were hampered by rising casualties and Japanese strengths in firepower and numbers. Combined with fatigue and a breakdown in communications, the garrison was gradually overwhelmed in the four day battle for the city, and finally collapsed on the night of December 12.[49]

On December 12, under heavy artillery fire and aerial bombardment, General Tang Sheng-chi ordered his men to retreat. Conflicting orders and a breakdown in discipline turned the events that followed into a disaster. While some Chinese units managed to escape across the river, many more were caught up in the general chaos erupting across the city. Some Chinese soldiers stripped civilians of their clothing in a desperate attempt to blend in, and many others were shot by the Chinese supervisory unit as they tried to flee.[34]

On December 13, the 6th and the 116th Divisions of the Japanese Army were the first to enter the city. Simultaneously, the 9th Division entered nearby Guanghua Gate, and the 16th Division entered the Zhongshan and Taiping gates. That same afternoon, two small Japanese Navy fleets arrived on both sides of the Yangtze River.

Pursuit and "mopping-up operations"

The conflict in Nanjing persisted beyond the night of December 12–13, following the Japanese Army's capture of the remaining gates and entrance into the city. The Japanese army continued to encounter sporadic resistance from remaining Chinese forces for several additional days. The Japanese military determined that they needed to eliminate any remaining Chinese soldiers hidden within the city. However, the search process used an arbitrary criteria for identifying former Chinese soldiers. Chinese males who were deemed to be in good health were automatically presumed to be a soldier. During this operation, Japanese forces committed atrocities against the Chinese population.[50]

The rounding-up and mass killings of male civilians and captured POWs were referred to euphemistically as "mopping-up operations" in Japanese communiqués, in a manner "just like the Germans were to talk about 'processing' or 'handling' Jews."[51]

Civilian population and evacuation

With the relocation of the capital of China, constant bombing raids, and reports of Japanese brutality, much of Nanjing's civilian population had fled out of fear. Wealthy families were the first to flee, leaving Nanjing in automobiles, followed by the evacuation of the middle class and then the poor. Those that remained were mainly the destitute lowest class such as the ethnic Tanka boat people, and those with assets that could not be easily moved, like shopkeepers.[8]

Of Nanjing's population, estimated to be over one million before the Japanese invasion, half had already fled Nanjing before the Japanese arrived.[52][53]

Massacre

| Nanjing Massacre | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 南京大屠殺 | ||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 南京大屠杀 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||

| Kanji | 1. 南京大虐殺 2. 南京事件 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

From December 13, 1937, the Japanese Army engaged in random murder, torture, wartime rape, looting, arson, and other war crimes. Such crime continued from three to six weeks depending on the types of crime. The first three weeks were more intense.[a] A group of foreign expatriates headed by Rabe had formed a 15-man International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone on November 22 and mapped out the Nanking Safety Zone in order to safeguard civilians in the city.[55]

In a diary entry from Minnie Vautrin on December 15, 1937, she wrote about her experiences in the Safety Zone:

The Japanese have looted widely yesterday and today, have destroyed schools, have killed citizens, and raped women. One thousand disarmed Chinese soldiers, whom the International Committee hoped to save, were taken from them and by this time are probably shot or bayoneted. In our South Hill House Japanese broke the panel of the storeroom and took out some old fruit juice and a few other things.[39]

Causes

The Nanjing Massacre's occurrence and nature were influenced by several factors. The Japanese population was taught militaristic and racist ideologies. The Japanese government's fascist doctrine further propagated the belief in Japanese superiority over all other peoples. Other factors include the cruel treatment of Japanese soldiers by their commanders and the challenging combat environment in China.[56]

The Nanjing Massacre happened during Japan's invasion of China. The extreme cruelty witnessed in Nanjing, including extensive killing, torture, sexual violence, and looting, was not an isolated occurrence, but rather a reflection of Japan's behavior throughout the war in China. This violence cannot be separated from the underlying contempt for other Asians that was deeply ingrained in Japanese society before the war.[57] To demonstrate the profound effects of ethnic prejudice, Japanese author Tsuda Michio gives an example:

During the war in south China, a Japanese sergeant who had raped and killed numerous Chinese women became 'impotent' as soon as he found out to his shock that one of his victims was actually a Japanese woman who had married a Chinese man and emigrated to China.[57]

Shiro Azuma, a former Japanese soldier, testified in a 1998 interview:

When I tried to cut off the first one, either the farmer moved or I mis-aimed. I ended up slicing off just part of his skull. Blood spurted upwards. I swung again... and this time I killed him... We were taught that we were a superior race since we lived only for the sake of a human god—our emperor. But the Chinese were not. So we held nothing but contempt for them... There were many rapes, and the women were always killed. When they were being raped, the women were human. But once the rape was finished, they became pig's flesh.[58]

Jonathan Spence, a British-American sinologist and historian, wrote:

[T]here is no obvious explanation for this grim event, nor can one be found. The Japanese soldiers, who had expected easy victory, instead had been fighting hard for months and had taken infinitely higher casualties than anticipated. They were bored, angry, frustrated, tired. The Chinese women were undefended, their menfolk powerless or absent. The war, still undeclared, had no clear-cut goal or purpose. Perhaps all Chinese, regardless of sex or age, seemed marked out as victims.[59]

Jennifer M. Dixon, Associate Professor in the Department of Political Science at Villanova University, stated:

In addition, the Battle of Shanghai which preceded the capture of Nanjing, was more difficult and prolonged than the Japanese side had anticipated, which contributed to a desire among Japanese officers and soldiers to exact revenge on the Chinese.[56]

Prime Minister Fumimaro Konoe, who presided over the Second Sino-Japanese War,[60] justified the massacre as retaliation against persistent Kuomintang aggression,[61] and advocated for the regime's destruction in January 1938.[62] Prior to the fall of Nanjing, Konoe rejected Chiang Kai-Shek's offer of negotiation through a German ambassador.[61]

Massacre contest

In 1937, the Osaka Mainichi Shimbun and its sister newspaper, the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun, covered a contest between two Japanese officers, Toshiaki Mukai and Tsuyoshi Noda of the Japanese 16th Division. The two men were described as vying to be the first to kill 100 people with a sword before the capture of Nanjing. From Jurong, Jiangsu to Tangshan, Mukai had killed 89 people while Noda had killed 78. The contest continued because neither had killed 100 people. By the time they had arrived at Purple Mountain, Noda had killed 105 people while Mukai had killed 106 people. Both officers supposedly surpassed their goal during the heat of battle, making it impossible to determine which officer had actually won the contest. Therefore, according to journalists Asami Kazuo and Suzuki Jiro, writing in the Tokyo Nichi Nichi Shimbun of December 13, they decided to begin another contest to kill 150 people.[63]

Rape

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East estimated that in the first month of the occupation, Japanese soldiers committed approximately 20,000 cases of rape in the city.[66] Some estimates claim 80,000 cases of rape.[3] According to the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, rapes of all ages, including children and elderly women, were commonplace, and there were many instances of sadistic and violent behavior related to these rapes. Following the rapes, many women were killed and their bodies were mutilated.[67] A large number of rapes were done systematically by the Japanese soldiers as they went from door to door, searching for girls, with many women being captured and gang-raped.[68]

Japanese soldier Takokoro Kozo recalled:

Women suffered most. No matter how young or old, they all could not escape the fate of being raped. We sent out coal trucks to the city streets and villages to seize a lot of women. And then each of them was allocated to fifteen to twenty soldiers for sexual intercourse and abuse. After raping we would also kill them.[69]

The women were often killed immediately after being raped, often through explicit mutilation,[70] such as by penetrating vaginas with bayonets, long sticks of bamboo, or other objects. For example, a six-months pregnant woman was stabbed sixteen times in the face and body, one stab piercing and killing her unborn child. A young woman had a beer bottle rammed up her vagina after being raped, and was then shot. Edgar Snow wrote how "discards were often bayoneted by drunken Japanese soldiers."[71]

On December 19, 1937, the Reverend James M. McCallum wrote in his diary:[72]

I know not where to end. Never I have heard or read such brutality. Rape! Rape! Rape! We estimate at least 1,000 cases a night and many by day. In case of resistance or anything that seems like disapproval, there is a bayonet stab or a bullet... People are hysterical... Women are being carried off every morning, afternoon and evening. The whole Japanese army seems to be free to go and come as it pleases, and to do whatever it pleases.

A fifteen-year-old girl was locked naked in a barracks housing two hundred to three hundred Japanese soldiers and raped multiple times daily. American correspondent Edgar Snow wrote how "Frequently mothers had to watch their babies beheaded, and then submit to raping." YMCA head Fitch reported that a woman "had her five-months infant deliberately smothered by the brute to stop it crying while he raped her."[71]

On March 7, 1938, Robert O. Wilson, a surgeon at the university hospital in the Safety Zone administrated by the United States, wrote in a letter to his family, "a conservative estimate of people slaughtered in cold blood is somewhere about 100,000, including of course thousands of soldiers that had thrown down their arms."[73] Here are two excerpts from his letters of December 15 and 18, 1937 to his family:[74][page needed]

The slaughter of civilians is appalling. I could go on for pages telling of cases of rape and brutality almost beyond belief. Two bayoneted corpses are the only survivors of seven street cleaners who were sitting in their headquarters when Japanese soldiers came in without warning or reason and killed five of their number and wounded the two that found their way to the hospital. Let me recount some instances occurring in the last two days. Last night, the house of one of the Chinese staff members of the university was broken into and two of the women, his relatives, were raped. Two girls, about 16, were raped to death in one of the refugee camps. In the University Middle School where there are 8,000 people the Japs came in ten times last night, over the wall, stole food, clothing, and raped until they were satisfied. They bayoneted one little boy of eight who [had] five bayonet wounds including one that penetrated his stomach, a portion of omentum was outside the abdomen. I think he will live.

In his diary kept during the aggression against the city and its occupation by the Imperial Japanese Army, the leader of the Safety Zone, John Rabe, wrote many comments about Japanese atrocities. For December 17:[75]

Two Japanese soldiers have climbed over the garden wall and are about to break into our house. When I appear they give the excuse that they saw two Chinese soldiers climb over the wall. When I show them my party badge, they return the same way. In one of the houses in the narrow street behind my garden wall, a woman was raped, and then wounded in the neck with a bayonet. I managed to get an ambulance so we can take her to Kulou Hospital... Last night up to 1,000 women and girls are said to have been raped, about 100 girls at Ginling College...alone. You hear nothing but rape. If husbands or brothers intervene, they're shot. What you hear and see on all sides is the brutality and bestiality of the Japanese soldiers.

In a documentary film about the Nanjing Massacre, In the Name of the Emperor, a former Japanese soldier named Shiro Azuma spoke candidly about the process of rape and murder in Nanjing.[76]

At first we used some kinky words like Pikankan. Pi means "hip," kankan means "look." Pikankan means, "Let's see a woman open up her legs." Chinese women didn't wear under-pants. Instead, they wore trousers tied with a string. There was no belt. As we pulled the string, the buttocks were exposed. We "pikankan." We looked. After a while we would say something like, "It's my day to take a bath," and we took turns raping them. It would be all right if we only raped them. I shouldn't say all right. But we always stabbed and killed them. Because dead bodies don't talk.

Iris Chang, author of the book Rape of Nanjing, wrote one of the most comprehensive accounts of Japanese war atrocities in China.[77] In her book, she estimated that the number of Chinese women raped by Japanese soldiers ranged from 20,000 to 80,000. Chang also states that not all rape victims were women. Some Chinese men were sodomized and forced to perform "repulsive sex acts".[78][79] There are also accounts of Japanese troops coercing families into committing incestuous acts; sons were forced to rape their mothers, fathers their daughters, and brothers their sisters. Other family members would be forced to look on.[80][81] Instead of punishing the Japanese troops who were responsible for wholesale rape, "'The Japanese expeditionary Force in Central China issued an order to set up comfort houses during this period of time,' Yoshimi Yoshiaki, a prominent history professor at Chuo University, observes, 'because Japan was afraid of criticism from China, the United States of America and Europe following the case of massive rapes between battles in Shanghai and Nanjing.'"[82]

Massacre of civilians

For about three weeks since December 13, 1937,[6] the Imperial Japanese Army entered the Nanking Safety Zone to search for former Chinese soldiers hidden among refugees. Many innocent men were misidentified and killed.[6]

John Rabe summarized the behavior of Japanese troops in Nanjing in his diaries:

I've written several times in this diary about the body of the Chinese soldier who was shot while tied to his bamboo bed and who is still lying unburied near my house. My protests and pleas to the Japanese embassy finally to get this corpse buried, or give me permission to bury it, have thus far been fruitless. The body is still lying in the same spot as before, except that the ropes have been cut and the bamboo bed is now lying about two yards away. I am totally puzzled by the conduct of the Japanese in this matter. On the one hand, they want to be recognized and treated as a great power on a par with European powers, on the other, they are currently displaying a crudity, brutality, and bestiality that bears no comparison except with the hordes of Genghis Khan. I have stopped trying to get the poor devil buried, but i hereby record that he, though very dead, still lies above the earth![83]

The death toll of civilians is difficult to precisely calculate due to the many bodies deliberately burnt, buried in mass graves, or dumped into the Yangtze River.[84][85] Robert O. Wilson, a physician, testified that cases of gun wounds "continued to come in [to the hospital of University of Nanjing] for a matter of some six or seven weeks following the fall of the city on December 13, 1937. The capacity of the hospital was normally one hundred and eighty beds, and this was kept full to overflowing during this entire period.[86] Bradley Campbell described the Nanjing Massacre as a genocide, given the fact that residents were still slaughtered en masse during the aftermath, despite the successful and certain outcome in battle.[87] However, Jean-Louis Margolin does not believe that the Nanjing atrocities should be considered a genocide because only prisoners of war were executed in a systematic manner and the targeting of civilians was sporadic and done without orders by individual actors.[88] On December 13, 1937, John Rabe wrote in his diary:

It is not until we tour the city that we learn the extent of destruction. We come across corpses every 100 to 200 yards. The bodies of civilians that I examined had bullet holes in their backs. These people had presumably been fleeing and were shot from behind. The Japanese march through the city in groups of ten to twenty soldiers and loot the shops... I watched with my own eyes as they looted the café of our German baker Herr Kiessling. Hempel's hotel was broken into as well, as [was] almost every shop on Chung Shang and Taiping Road.[89]

American vice consul James Espy arrived in Nanjing on January 6, 1938, to reopen the American embassy. He gave a summarized description of what happened in the city:

The picture that they painted of Nanking was one of a reign of terror that befell the city upon its occupation by the Japanese military forces. Their stories and those of the German residents tell of the city having fallen into the hands of the Japanese as captured prey, not merely taken in the course of organized warfare but seized by an invading army whose members seemed to have set upon the prize to commit unlimited depredations and violence. Fuller data and our own observations have not brought out facts to discredit their information. The civilian Chinese population remaining in the city crowded the streets of the so-called "safety zone" as refugees, many of whom are destitute. Physical evidences are almost everywhere to the killing of men, women and children, of the breaking into and looting of property and of the burning and destruction of houses and buildings.

It remains, however, the Japanese soldiers swarmed over the city in thousands and committed untold depredations and atrocities. It would seem according to stories told us by foreign witnesses that the soldiers were let loose like a barbarian horde to desecrate the city. Men, women and children were killed in uncounted numbers throughout the city. Stories are heard of civilians being shot or bayoneted for no apparent reason.[90]

On February 10, 1938, Legation Secretary of the German Embassy, Georg Rosen, wrote to his Foreign Ministry about a film made in December by Reverend John Magee to recommend its purchase.

During the Japanese reign of terror in Nanjing—which, by the way, continues to this day to a considerable degree—the Reverend John Magee, a member of the American Episcopal Church Mission who has been here for almost a quarter of a century, took motion pictures that eloquently bear witness to the atrocities committed by the Japanese... One will have to wait and see whether the highest officers in the Japanese army succeed, as they have indicated, in stopping the activities of their troops, which continue even today.[89] On December 13, about 30 soldiers came to a Chinese house at No. 5 Hsing Lu Koo in the southeastern part of Nanjing and demanded entrance. The door was open by the landlord, a Mohammedan named Ha. They killed him immediately with a revolver and also Mrs. Ha, who knelt before them after Ha's death, begging them not to kill anyone else. Mrs. Ha asked them why they killed her husband and they shot her. Mrs. Hsia was dragged out from under a table in the guest hall where she had tried to hide with her 1-year-old baby. After being stripped and raped by one or more men, she was bayoneted in the chest and then had a bottle thrust into her vagina. The baby was killed with a bayonet. Some soldiers then went to the next room, where Mrs. Hsia's parents, aged 76 and 74, and her two daughters aged 16 and 14 [were]. They were about to rape the girls when the grandmother tried to protect them. The soldiers killed her with a revolver. The grandfather grasped the body of his wife and was killed. The two girls were then stripped, the elder being raped by 2–3 men and the younger by 3. The older girl was stabbed afterwards and a cane was rammed in her vagina. The younger girl was bayoneted also but was spared the horrible treatment that had been meted out to her sister and mother. The soldiers then bayoneted another sister of between 7–8, who was also in the room. The last murders in the house were of Ha's two children, aged 4 and 2 respectively. The older was bayoneted and the younger split down through the head with a sword.[89]

Pregnant women were targeted for murder, as their stomachs were often bayoneted, sometimes after rape. Tang Junshan, survivor and witness to one of the Japanese army's systematic mass killings, testified:[91]

The seventh and last person in the first row was a pregnant woman. The soldier thought he might as well rape her before killing her, so he pulled her out of the group to a spot about ten meters away. As he was trying to rape her, the woman resisted fiercely... The soldier abruptly stabbed her in the belly with a bayonet. She gave a final scream as her intestines spilled out. Then the soldier stabbed the fetus, with its umbilical cord clearly visible, and tossed it aside.

According to Navy veteran Sho Mitani, "The Army used a trumpet sound that meant 'Kill all Chinese who run away'."[92] Thousands were led away and mass-executed in an excavation known as the "Ten-Thousand-Corpse Ditch", a trench measuring about 300 m long and 5 m wide. Since records were not kept, estimates regarding the number of victims buried in the ditch range from 4,000 to 20,000.

The Hui people, a minority Chinese group, the majority of them Muslim, suffered as well during the massacre. One mosque was found destroyed and others found to be "filled with dead bodies." Hui volunteers and imams buried over a hundred of their dead following Muslim ritual.[93]

The Japanese massacred Hui Muslims in their mosques in Nanjing and destroyed Hui mosques in other parts of China.[94]

Extrajudicial killing of Chinese prisoners of war and male civilians

Soon after the fall of the city, Japanese troops made a thorough search for Chinese soldiers and summarily arrested thousands of young Chinese men. Many were taken to the Yangtze River, where they were machine-gunned to death. What was probably the single largest massacre of Chinese troops, the Straw String Gorge Massacre, occurred along the banks of the Yangtze River on December 18. For most of the morning, Japanese soldiers tied the POWs' hands together. At dusk, the soldiers divided POWs into four columns and opened fire. Unable to escape, the POWs could only scream and thrash desperately. It took an hour for the sounds of death to stop and even longer for the Japanese to bayonet each individual. The majority of the bodies were dumped directly into the Yangtze River.[95]

Japanese troops gathered 1,300 Chinese soldiers and civilians at Taiping Gate and murdered them. The victims were blown up with landmines, then doused with petrol and set on fire. The survivors were killed with bayonets.[96]

A soldier from the IJA's 13th division described killing survivors in his diary:[97]

"I figured that I'd never get another chance like this, so I stabbed thirty of the damned Chinks. Climbing atop the mountain of corpses, I felt like a real devil-slayer, stabbing again and again, with all my might. 'Ugh, ugh,' the Chinks groaned. There were old folks as well as kids, but we killed them lock, stock, and barrel. I also borrowed a buddy's sword and tried to decapitate some. I've never experienced anything so unusual."

U.S. news correspondents F. Tillman Durdin and Archibald Steele reported seeing corpses of massacred Chinese soldiers forming mounds six feet high at the Nanjing Yijiang gate in the north. Durdin, who worked for The New York Times, toured Nanjing before his departure from the city. He heard waves of machine-gun fire and witnessed the Japanese soldiers gun down some two hundred Chinese within ten minutes. He would later state that he had seen tank guns used on bound soldiers.

Two days later, in his report to The New York Times, Durdin stated that the alleys and streets were filled with the dead, amongst them women and children. Durdin stated "[i]t should be said that certain Japanese units exercised restraint and that certain Japanese officers tempered power with generosity and commission," but continued "the conduct of the Japanese army as a whole in Nanjing was a blot on the reputation of their country"."[98][99]

Ralph L. Phillips, a missionary, testified to the U.S. State Assembly Investigating Committee, that he was "forced to watch while the Japs disemboweled a Chinese soldier" and "roasted his heart and liver and ate them."[100]

Just after Christmas, the Japanese set up public stages where they called upon former Chinese soldiers to confess, claiming they would not be harmed. When over 200 former soldiers did come forward, they were promptly executed. When former soldiers stopped identifying themselves, the Japanese began rounding up groups of young men who "aroused suspicion."[101]

Based on the dutiful records of the Safety Zone committee, the post-war International Military Tribunal found that some 20,000 Chinese male civilians were killed on false accusations of being soldiers, while some 30,000 genuine former combatants were executed and their bodies thrown in the river.[102]

Looting and arson

"In the first days of the occupation the soldiers [...] took a great deal of bedding, cooking utensils and food from the refugees. Practically every building in the city was entered many, many times by these roving gangs of soldiers throughout the first six or seven weeks of the occupation".[6] "[T]here was no burning until the Japanese troops had been in the city five or six days. Beginning, I believe, on the 19th or 20th of December, burning was carried on regularly for six weeks."[6]

Stationed in Nanjing, an eyewitness, journalist F. Tillman of The New York Times, sent an article to his newspaper where he described the Imperial Japanese Army's entry into Nanjing in December 1937: "The plunder carried out by the Japanese reached almost the entire city. Almost all buildings were entered by Japanese soldiers, often in the sight of their officers, and the men took whatever they wanted. Japanese soldiers often forced Chinese to carry the loot."[103]

One-third of the city was destroyed as a result of arson. According to reports, Japanese troops torched newly built government buildings as well as the homes of many civilians. There was considerable destruction to areas outside the city walls. Soldiers pillaged from the poor and the wealthy alike. The lack of resistance from Chinese troops and civilians in Nanjing meant that the Japanese soldiers were free to divide up the city's valuables as they saw fit. This resulted in widespread looting and burglary.[104]

On December 17, chairman John Rabe wrote a complaint to Kiyoshi Fukui, second secretary of the Japanese Embassy. The following is an excerpt:

In other words, on the 13th when your troops entered the city, we had nearly all the civilian population gathered in a Zone in which there had been very little destruction by stray shells and no looting by Chinese soldiers even in full retreat... All 27 Occidentals in the city at that time and our Chinese population were totally surprised by the reign of robbery, raping and killing initiated by your soldiers on the 14th. All we are asking in our protest is that you restore order among your troops and get the normal city life going as soon as possible. In the latter process we are glad to cooperate in any way we can. But even last night between 8 and 9 p.m. when five Occidental members of our staff and Committee toured the Zone to observe conditions, we did not find any single Japanese patrol either in the Zone or at the entrances![105]

Nanking Safety Zone and the role of foreigners

The Japanese troops did respect the Zone to an extent; until the Japanese occupation, no shells entered that part of the city except a few stray shots. During the chaos following the attack of the city, some were killed in the Safety Zone, but the crimes that occurred in the rest of the city were far greater by all accounts.[106]

Rabe wrote that, from time to time, the Japanese would enter the Safety Zone at will, carry off a few hundred men and women, and either summarily execute them or rape and then kill them.[107]

By February 5, 1938, the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone had forwarded to the Japanese embassy a total of 450 cases of murder, rape, torture and general disorder by Japanese soldiers that had been reported after the American, British and German diplomats had returned to their embassies:[108]

- "Case 5 – On the night of December 14th, there were many cases of Japanese soldiers entering houses and raping women or taking them away. This created panic in the area and hundreds of women moved into the Ginling College campus yesterday."

- "Case 10 – On the night of December 15th, a number of Japanese soldiers entered the University of Nanjing buildings at Tao Yuen and raped 30 women on the spot, some by six men."

- "Case 13 – December 18, 4 p.m., at No. 18 I Ho Lu, Japanese soldiers wanted a man's cigarette case and when he hesitated, one of the soldier crashed in the side of his head with a bayonet. The man is now at the University Hospital and is not expected to live."

- "Case 14 – On December 16, seven girls (ages ranged from 16 to 21) were taken away from the Military College. Five returned. Each girl was raped six or seven times daily – reported December 18th."

- "Case 15 – There are about 540 refugees crowded in No. 83 and 85 on Canton Road... More than 30 women and girls have been raped. The women and children are crying all nights. Conditions inside the compound are worse than we can describe. Please give us help."

- "Case 16 – A Chinese girl named Loh, who, with her mother and brother, was living in one of the Refugee Centers in the Refugee Zone, was shot through the head and killed by a Japanese soldier. The girl was 14 years old. The incident occurred near the Kuling Ssu, a noted temple on the border of the Refugee zone ..."[108]

- "Case 19 – January 30th, about 5 p.m. Mr. Sone (of the Nanjing Theological Seminary) was greeted by several hundred women pleading with him that they would not have to go home on February 4th. They said it was no use going home they might just as well be killed for staying at the camp as to be raped, robbed or killed at home... One old woman 62 years old went home near Hansimen and Japanese soldiers came at night and wanted to rape her. She said she was too old. So the soldiers rammed a stick up her. But she survived to come back."

It is said that Rabe rescued between 200,000 and 250,000 Chinese people.[109][110]

-

Photo in the album taken in Nanjing by Itou Kaneo of the Kisarazu Air Unit of the Imperial Japanese Navy

-

A picture of a dead child. Probably taken by Bernhard Sindberg

-

Prisoners being buried alive[111]

-

Skeletons of the massacre's victims

-

A pond filled with dead victims

-

Another photo from Itou Kaneo's album, displaying Chinese corpses

Literature

Eyewitness accounts include testimonies of expatriates engaged in humanitarian work (mostly physicians, professors, missionary and businessmen), journalists (both Western and Japanese), as well as the field diaries of military personnel. American missionary John Magee stayed behind to provide a 16 mm film documentary and first-hand photographs of the Nanjing Massacre. Rabe and American missionary Lewis S. C. Smythe, secretary of the International Committee and a professor of sociology at the University of Nanjing, recorded the actions of the Japanese troops and filed complaints with the Japanese embassy.

Matsui's reaction to the massacre

On December 18, 1937, as General Iwane Matsui began to comprehend the full extent of the rape, torture, murder, and looting in the city, he grew increasingly dismayed. He reportedly told one of his civilian aides:

I now realize that we have unknowingly wrought a most grievous effect on this city. When I think of the feelings and sentiments of many of my Chinese friends who have fled from Nanjing and of the future of the two countries, I cannot but feel depressed. I am very lonely and can never get in a mood to rejoice about this victory... I personally feel sorry for the tragedies to the people, but the Army must continue unless China repents. Now, in the winter, the season gives time to reflect. I offer my sympathy, with deep emotion, to a million innocent people.

On New Year's Day, over a toast he confided to a Japanese diplomat: "My men have done something very wrong and extremely regrettable."[112] Matsui blamed the atrocities on the moral decline of the Japanese Army, saying:

The Nanjing Incident was a terrible disgrace... Immediately after the memorial services, I assembled the higher officers and wept tears of anger before them, as Commander-in-Chief... I told them that after all our efforts to enhance the Imperial prestige, everything had been lost in one moment through the brutalities of the soldiers. And can you imagine it, even after that, these officers laughed at me... I am really, therefore, quite happy that I, at least, should have ended this way, in the sense that it may serve to urge self-reflection on many more members of the military of that time.[113]

End of the massacre

In late January 1938, the Japanese army forced all refugees in the Safety Zone to return home, immediately claiming to have "restored order". After the establishment of the weixin zhengfu (Chinese: 维新政府; pinyin: Wéixīn zhèngfǔ) (the collaborating government) in 1938, order was gradually restored in Nanjing and atrocities by Japanese troops lessened considerably.[citation needed]

On February 18, 1938, the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone was forcibly renamed the Nanjing International Rescue Committee, and the Safety Zone effectively ceased to function. The last refugee camps were closed in May 1938.[citation needed]

Recall of Matsui and Asaka

In February 1938, both Prince Asaka and General Matsui were recalled to Japan. Matsui returned to retirement, but Prince Asaka remained on the Supreme War Council until the end of the war in August 1945. He was promoted to the rank of general in August 1939, though he held no further military commands.[45]

Evidence collection

The Japanese either destroyed or concealed important documents, severely reducing the amount of evidence available for confiscation. Between the declaration of a ceasefire on August 15, 1945, and the arrival of American troops in Japan on August 28, "the Japanese military and civil authorities systematically destroyed military, naval, and government archives, much of which was from the period 1942–1945."[114] Overseas troops in the Pacific and East Asia were ordered to destroy incriminating evidence of war crimes.[114] Approximately 70 percent of the Japanese army's wartime records were destroyed.[114] In regards to the Nanjing Massacre, Japanese authorities deliberately concealed wartime records, eluding confiscation from American authorities.[115] Some of the concealed information was made public a few decades later. For example, a two-volume collection of military documents related to the Nanjing operations was published in 1989; and disturbing excerpts from Kesago Nakajima's diary, a commander at Nanjing, was published in the early 1980s.[115]

During his time in China, Bernhard Arp Sindberg, an amateur photographer and friend to several foreign journalists, always had his camera with him, taking graphic photos of the civilian massacres and extensive destruction.[116] Sindberg smuggled the unprocessed film out of China with the help of his company, and had entrusted the development of the film to his colleagues. After the war, he retrieved his photos, producing one of the few photographic records documenting the Nanjing massacre.[116]

Ono Kenji, a chemical worker in Japan, procured a collection of wartime diaries from Japanese veterans who fought in the Battle of Nanking in 1937.[117] In 1994, nearly 20 diaries in his collection were published, which became an important source of evidence for the massacre. Official war journals and diaries were also published by Kaikosha, an organization of retired Japanese military veterans.[117]

In 1984, in an attempt to refute Japanese war crimes in Nanjing, Kaikosha, the Japanese Army Veterans Association, interviewed former Japanese soldiers who had served in the Nanjing area from 1937 to 1938. Instead of refuting the massacre, the interviewed veterans confirmed that a massacre had taken place and openly described and admitted to taking part in the atrocities. In 1985, the interviews were published in the association's magazine, Kaiko, along with an admission and apology that read, "Whatever the severity of war or special circumstances of war psychology, we just lose words faced with this mass illegal killing. As those who are related to the prewar military, we simply apologize deeply to the people of China. It was truly a regrettable act of barbarity."[118]

In early 1980s, after interviewing Chinese survivors and reviewing Japanese records, Japanese journalist Honda Katsuichi concluded that the Nanjing Massacre was not an isolated case, and that Japanese atrocities against the Chinese were common throughout the Lower Yangtze River since the battle of Shanghai.[119] The diaries of other Japanese combatants and medics who fought in China have corroborated his conclusions.[120]

Death toll estimates

Numerous factors complicate the estimation of an accurate death toll.[121][122]

According to American historian Edward J. Drea:

While the Germans, beginning in 1943, did engage in substantial efforts to obliterate evidence of such crimes as mass murder, and they destroyed a great deal of potentially incriminating records in 1945, a great deal survived, in part because not each one of the multiple copies had been burned. The situation was different in Japan. Between the announcement of a ceasefire on August 15, 1945, and the arrival of small advance parties of American troops in Japan on August 28, Japanese military and civil authorities systematically destroyed military, naval, and government archives, much of which was from the period 1942–1945. Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo dispatched enciphered messages to field commands throughout the Pacific and East Asia ordering units to burn incriminating evidence of war crimes, especially offenses against prisoners of war.[121]

According to Yang Daqing, professor of History and International Affairs at George Washington University:

While it is standard practice for governments to destroy evidence in times of defeat, in the two weeks before the Allies arrived in Japan, various Japanese agencies—the military in particular—systematically destroyed sensitive documents to a degree perhaps unprecedented in history. Estimates of the impact of the destruction vary. Tanaka Hiromi, a professor at Japan’s National Defense Academy who has conducted extensive research into remaining Imperial Japanese Army and Navy documents in Japan and overseas, claims that less than 0.1 percent of the material ordered for destruction survived.[123]

In 2003, the director of Japan's Military History Archives of National Institute for Defense Studies said that as much 70 percent of Japan's wartime records were destroyed.[121]

Other factors include the mass disposal of Chinese corpses by Japanese soldiers; the revisionist tendencies of both Chinese and Japanese individuals and groups, who are driven by nationalistic and political motivations; and the subjectivity involved in the collection and interpretation of evidence.[3][124][122][125] However, the most credible scholars in Japan, which include a large number of authoritative academics, support the validity of the International Military Tribunal for the Far East and its findings, which estimate more than 100,000 casualties.[124]

Historian Tokushi Kasahara states "more than 100,000 and close to 200,000, or maybe more."[126] With the emergence of more information and data, he said that there is a possibility that the death toll could be higher. Hiroshi Yoshida concludes "more than 200,000" in his book.[127] Tomio Hora supports the information found in the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, which estimates a death toll of at least 200,000.[128][129] An estimate death toll of 300,000 has also been cited.[84]

According to the International Military Tribunal for the Far East, estimates made at a later date indicate that the total number of civilians and prisoners of war murdered in Nanjing and its vicinity during the first six weeks of the Japanese occupation was over 200,000. These estimates are borne out by the figures of burial societies and other organizations, which testify to over 155,000 buried bodies. These figures also do not take into account those persons whose bodies were destroyed by burning, drowning or other means, or whose bodies were interred in mass graves.[85] The most credible scholars in Japan, which include a large number of authoritative academics, support the validity of the tribunal and its findings.[124]

According to the verdict of the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal on March 10, 1947, there are "more than 190,000 mass slaughtered civilians and Chinese soldiers killed by machine gun by the Japanese army, whose corpses have been burned to destroy proof. Besides, we count more than 150,000 victims of barbarian acts buried by the charity organizations. We thus have a total of more than 300,000 victims."[130]

John Rabe, Chairman of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone, estimated that between 50,000 and 60,000 (civilians) were killed.[131] However, Erwin Wickert, the editor of The diaries of John Rabe, points out that "It is likely that Rabe's estimate is too low, since he could not have had an overview of the entire municipal area during the period of the worst atrocities. Moreover, many troops of captured Chinese soldiers were led out of the city and down to the Yangtze, where they were summarily executed. But, as noted, no one actually counted the dead."

Harold Timperley, a journalist in China during the Japanese invasion, reported that at least 300,000 Chinese civilians were killed in Nanjing and elsewhere, and tried to send a telegram but was censored by the Japanese military in Shanghai.[132] Other sources, including Iris Chang's The Rape of Nanjing, also conclude that the death toll reached 300,000. In December 2007, newly declassified U.S. government archive documents revealed that a telegraph by the U.S. ambassador to Germany in Berlin sent one day after the Japanese army occupied Nanjing, stated that he heard the Japanese ambassador in Germany boasting that the Japanese army had killed 500,000 Chinese soldiers and civilians as the Japanese army advanced from Shanghai to Nanjing. According to the archives research "The telegrams sent by the U.S. diplomats [in Berlin] pointed to the massacre of an estimated half a million people in Shanghai, Suzhou, Jiaxing, Hangzhou, Shaoxing, Wuxi and Changzhou".[133][134]

According to documents in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register, at least 300,000 Chinese were killed.[135][136]

Range and duration

The duration of the incident is naturally defined by its geography: the earlier the Japanese entered the area, the longer the duration. The Battle of Nanking ended on December 13, when the divisions of the Japanese Army entered the walled city of Nanjing. The Tokyo War Crime Tribunal defined the period of the massacre to the ensuing six weeks. More conservative estimates say that the massacre started on December 14, when the troops entered the Safety Zone, and that it lasted for six weeks. Historians who define the Nanjing Massacre as having started from the time that the Japanese Army entered Jiangsu province push the beginning of the massacre to around mid-November to early December (Suzhou fell on November 19), and extended the end of the massacre to late March 1938.[citation needed]

To many Japanese scholars, post-war estimations were distorted by "victor's justice", when Japan was condemned as the sole aggressor. They believed the 300,000 toll typified a "Chinese-style exaggeration" with disregard for evidence. Yet, in China, this figure has come to symbolize the justice, legality, and authority of the post-war trials condemning Japan as the aggressor.[137]

War crimes tribunals

Shortly after the surrender of Japan, the primary officers in charge of the Japanese troops at Nanjing were put on trial. General Matsui was indicted before the International Military Tribunal for the Far East for "deliberately and recklessly" ignoring his legal duty "to take adequate steps to secure the observance and prevent breaches" of the Hague Convention.

Other Japanese military leaders in charge at the time of the Nanjing Massacre were not tried. Prince Kan'in Kotohito, chief of staff of the Imperial Japanese Army during the massacre, had died before the end of the war in May 1945. Prince Asaka was granted immunity because of his status as a member of the imperial family.[138][139] Isamu Chō, the aide to Prince Asaka, and whom some historians believe issued the "kill all captives" memo, had committed seppuku (ritual suicide) during the Battle of Okinawa.[140]

-

The International Military Tribunal for the Far East was convened at "Ichigaya Court," formally Imperial Japanese Army HQ building in Ichigaya, Tokyo.

-

General Iwane Matsui[141]

-

General Hisao Tani[142]

Grant of immunity to Prince Asaka

On May 1, 1946, SCAP officials interrogated Prince Asaka, who was the ranking officer in the city at the height of the atrocities, about his involvement in the Nanjing Massacre and the deposition was submitted to the International Prosecution Section of the Tokyo tribunal. Asaka denied the existence of any massacre and claimed never to have received complaints about the conduct of his troops.[143]

Evidence and testimony

The prosecution began the Nanjing phase of its case in July 1946. Dr. Robert O. Wilson, a surgeon and a member of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone, testified.[144] Other members of the International Committee for the Nanking Safety Zone who took the witness stand included Miner Searle Bates[145] and John Magee.[146] George A. Fitch,[147] Lewis S. C. Smythe,[148] and James McCallum filed affidavits with their diaries and letters.[149]

The entry for the same day in Matsui's diary read, "I could only feel sadness and responsibility today, which has been overwhelmingly piercing my heart. This is caused by the Army's misbehaviors after the fall of Nanjing and failure to proceed with the autonomous government and other political plans."[150]

Matsui's defense

This section relies largely or entirely on a single source. (June 2016) |

Matsui asserted that he had never ordered the execution of Chinese POWs. He further argued that he had directed his army division commanders to discipline their troops for criminal acts, and was not responsible for their failure to carry out his directives. At trial, Matsui went out of his way to protect Prince Asaka by shifting blame to lower-ranking division commanders.[151]

Verdict

Kōki Hirota, Prime Minister of Japan at an earlier stage of the war, and a diplomat during the atrocities at Nanjing, was convicted of participating in "the formulation or execution of a common plan or conspiracy" (count 1), waging "a war of aggression and a war in violation of international laws, treaties, agreements and assurances against the Republic of China" (count 27) and count 55. Matsui was convicted by a majority of the judges at the Tokyo tribunal who ruled that he bore ultimate responsibility for the "orgy of crime" at Nanjing because, "He did nothing, or nothing effective, to abate these horrors."

Organized and wholesale murder of male civilians was conducted with the apparent sanction of the commanders on the pretext that Chinese soldiers had removed their uniforms and were mingling with the population. Groups of Chinese civilians were formed, bound with their hands behind their backs, and marched outside the walls of the city where they were killed in groups by machine gun fire and with bayonets. — From Judgment of the International Military Tribunal

Sentence

On November 12, 1948, Matsui and Hirota, along with five other convicted Class-A war criminals, were sentenced to death by hanging. Eighteen others received lesser sentences. The death sentence imposed on Hirota, a six-to-five decision by the eleven judges, shocked the general public and prompted a petition on his behalf, which soon gathered over 300,000 signatures but did not succeed in commuting the Minister's sentence. All of them were hanged on December 23, 1948.[152][153]

Other trials

Hisao Tani, a lieutenant general for the 6th Division of the Imperial Japanese Army, was tried by the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal in China.[151] He was found guilty of war crimes, sentenced to death, and executed by shooting on April 26, 1947. However, according to historian Tokushi Kasahara, the evidence used to convict Hisao Tani was not convincing.[154] Kasahara said that if there was a full investigation of the massacre, many other high ranking authorities, which include higher level commanders, army leaders and emperor Hirohito, could have been implicated.[154]

In 1947, Toshiaki Mukai and Tsuyoshi Noda, the two officers responsible for the contest to kill 100 people, were both arrested and extradited to China. They were also tried by the Nanjing War Crimes Tribunal. On trial with them was Gunkichi Tanaka, a captain from the 6th Division who personally killed over 300 Chinese POWs and civilians with his sword during the massacre. All three men were found guilty of war crimes and sentenced to death. They were executed by shooting together on January 28, 1948.[155][156]

Moritake Tanabe, the Chief of Staff of the Japanese 10th Army at the time of the massacre, was tried for unrelated war crimes in the Dutch East Indies. He was sentenced to death and executed in 1949.[157]

Memorials

- In 1985, the Memorial Hall for Nanjing Massacre victims was built by the Nanjing Municipal Government in remembrance of the victims and to raise awareness of the Nanjing Massacre. It is located near a site where thousands of bodies were buried, called the "pit of ten thousand corpses" wàn rén kēng (Chinese: 万人坑; pinyin: Wàn rén kēng). As of December 2016[update], there is a total of 10,615 Nanjing Massacre victim names inscribed on a memorial wall.[158]

- In 1995, Daniel Kwan held a photo exhibit in Los Angeles titled, "The Forgotten Holocaust".

- In 2005, John Rabe's former residence in Nanjing was renovated and now accommodates the "John Rabe and International Safety Zone Memorial Hall", which opened in 2006.

- On December 13, 2009, both the Chinese and Japanese monks held a religious assembly to mourn Chinese civilians killed by invading Japanese troops.[159]

- On December 13, 2014, China held its first Nanjing Massacre Memorial Day.[160]

On October 9, 2015, Documents of the Nanjing Massacre have been listed on the UNESCO Memory of the World Register.[136]

-

Yanziji Nanjing Massacre Memorial in 2004

-

A statue titled "Family Ruined" in front of the Nanjing Massacre Memorial Hall

-

John Rabe's former residence, now the "John Rabe and International Safety Zone Memorial Hall", in Nanjing, September 2010

Controversy

According to Japanese historian Fujiwara Akira, "When Japan accepted the Potsdam Declaration and surrendered in August 1945, the state officially acknowledged the war of aggression and the Nanjing massacre committed by the Japanese army."[161]

Debate in Japan

David Askew, formerly an associate professor at Ritsumeikan Asia Pacific University, noted that in Japan views concerning the massacre were divided between two mutually exclusive groups. The "Great Massacre School" group accepts the findings of the Tokyo Trials, and concludes that there were at least 200,000 casualties and at least 20,000 rape cases; whereas "The Illusion School" group rejects the tribunal's findings as "victor's justice". According to Askew, the "Great Massacre School" is more sophisticated, and the credibility of its conclusions are supported by a large number of authoritative academics.[162] Askew estimates that the city's population was 224,500 from December 24, 1937, to January 5, 1938.[163]

Hora Tomio, a Japanese history professor at Waseda University, published a book in 1967 following his 1966 visit to China, devoting a third of the book to the massacre.[164] During the 1970s, Katsuichi Honda wrote a series of articles for the Asahi Shimbun on war crimes committed by Japanese soldiers during World War II (such as the Nanjing Massacre).[165] In response, Shichihei Yamamoto, using the pen name "Isaiah Ben-Dasan", wrote an article that denied the massacre, and Akira Suzuki published a book that denied the massacre.[166] However, the debate was short-lived because no denialist produced a study that was as comprehensive as the one conducted by Hora.[166] The opposition was unable to present enough evidence to deny the massacre.[166]

There are disputes about the official death toll of the massacre. This estimate includes an estimation that the Japanese Army murdered 57,418 Chinese POWs at Mufushan, though the latest research indicates that between 4,000 and 20,000 were massacred,[7][167] and it also includes the 112,266 corpses apparently buried by the Chongshantang, a charitable association, though today some historians argue that the Chongshantang's records were at least greatly exaggerated if not entirely fabricated.[168][169][170] According to Bob Wakabayashi, he estimates the death toll within Nanjing City Wall to be around 40,000, mostly massacred in the first five days; while the total victims after a 3-month period in Nanjing and its surrounding six rural counties "far exceed 100,000 but fall short of 200,000".[124] Wakabayashi concludes that estimates of over 200,000 are not credible.[169]

Denials of the massacre in Japan

For the past several decades, Japanese politicians who express no remorse for the Nanjing massacre have exacerbated ongoing tensions in Sino-Japanese relations, with numerous Japanese government officials and a few historians in Japan either denying or dismissing the atrocity.[171][172][173][174]

Numerous scholars have stated that the Japanese Wikipedia version of the article (南京事件) contains revisionist and denialist narratives.[175][176][177][178] They note that the article notably lacks pictures and expresses doubt about the massacre in the first paragraph of the article. In 2021, Yumiko Sato translated a sentence from the first paragraph: "The Chinese side calls it the Nanjing Massacre, but the truth of the incident is still unknown".[177][178]

Legacy

Effect on international relations

The memory of the Nanjing Massacre has been a point of contention in Sino-Japanese relations since the early 1970s.[179] Trade between the two nations is worth over $200 billion annually. Despite this, many Chinese people still have a strong sense of mistrust due to the memory of the atrocity and failure of reconciliation measures. This sense of mistrust is strengthened by Japan's unwillingness to admit to and apologize for the atrocities.[180]

Takashi Yoshida described how changing political concerns and perceptions of the "national interest" in Japan, China, and the U.S. have shaped the collective memory of the Nanjing massacre. Yoshida contended that over time the event has acquired different meanings to different people. People from mainland China saw themselves as the victims. For Japan, it was a question they needed to answer but were reluctant to do so because they too identified themselves as victims after the A-bombs. The U.S., which served as the melting pot of cultures and is home to descendants of members of both Chinese and Japanese cultures, took up the mantle of investigator for the victimized Chinese. Yoshida had argued that the Nanjing Massacre had figured in the attempts of all three nations as they work to preserve and redefine national and ethnic pride and identity, assuming different kinds of significance based on each country's changing internal and external enemies.[181]

Many Japanese prime ministers have visited the Yasukuni Shrine, a shrine for Japanese war deaths up until the end of the Second World War, which includes war criminals that were involved in the Nanjing Massacre. In the museum adjacent to the shrine, a panel informs visitors that there was no massacre in Nanjing, but that Chinese soldiers in plain clothes were "dealt with severely". In 2006 former Japanese prime minister Junichiro Koizumi made a pilgrimage to the shrine despite warnings from China and South Korea. His decision to visit the shrine regardless sparked international outrage. Although Koizumi denied that he was trying to glorify war or historical Japanese militarism, the Chinese Foreign Ministry accused Koizumi of "wrecking the political foundations of China-Japan relations". An official from South Korea said they would summon the Tokyo ambassador to protest.[182][183]

The Massacre is contentiously compared to other disasters in China, which include the Great Chinese famine (1959–1961)[184][185][186] and the Cultural Revolution.[187][188][189]

As a component of national identity

Yoshida asserts that "Nanjing has figured in the attempts of all three nations [China, Japan and the United States] to preserve and redefine national and ethnic pride and identity, assuming different kinds of significance based on each country's changing internal and external enemies."[190]

China

Iris Chang, In her book Rape of Nanjing, asserted that the politics of the Cold War encouraged Chairman Mao to stay relatively silent about Nanjing in order to keep a trade relationship with Japan.[191] Jung Chang and Jon Halliday's biography of Mao claims Mao never made any comment either contemporaneously or later in his life about the massacre, but did frequently remark with enduring bitterness about a political struggle between himself and Wang Ming which also occurred in December 1937.[192]

Before the 1970s, China did relatively little to draw attention to the Nanjing massacre. There was also virtually no public commemoration until after 1982.[193] However, China was not oblivious to the Japanese debate over the massacre.[194] In 1982, concerned with Japanese denialism, accounts of the Nanjing Massacre, alongside other wartime atrocities committed by Japan in China, emerged in the Chinese media.[194] Concerns regarding Japanese denialism about the massacre was not confined solely to the People's Republic of China; scholars in Taiwan also initiated a response, publishing many studies about Japanese atrocities in China.[194]

According to American journalist Howard W. French, mentioning of the massacre was suppressed in China because ideologically the communists would rather promote the "martyrs of class struggles" than wartime victims, especially when there were no communist heroes or any communists at all in Nanjing when the massacre happened.[195]

According to Guo-Qiang Liu and Fengqi Qian of Deakin University, only since the 1990s, through the revisionist Patriotic Education Campaign, the massacre had become a national memory as an episode of the "Century of Humiliation" prior to the communist founding of a "New China". This orthodox victimhood narrative has become entwined with the Chinese national identity and is very sensitive to the revisionist sentiments from the far-right in Japan, which makes the memory of the massacre a recurring point of tension in Sino-Japanese relations after 1982.[196]

Japan

Following the end of World War II, some circles of civil society in Japan reflected on the extent of the massacre and the participation of ordinary soldiers. Notably, the novelist Hotta Yoshie wrote a novel, Time (Jikan) in 1953, portraying the massacre from the point of view of a Chinese intellectual watching it happen. This novel has been translated into Chinese and Russian. Other eyewitnesses to the massacre also expressed their opinions in Japanese magazines in the 1950s and 1960s, but political shifts slowly eroded this tide of confessions.